Articles

Fathers know best? Phil Lord and Chris Miller’s surprising animated dads

Particularly striking to me, and even moving, is a theme connecting Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs and Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (though not The Lego Movie): how themes of father–son conflict ubiquitous in other cartoons play out with unexpectedly insightful, consequential fathers.

2018: The year in reviews

2018 was a remarkable movie year — for family films, films with religious themes, and documentaries — but it was also a year of family men who weren’t there for their families.

The Dark Knight trilogy: The inconclusive battle for Gotham’s soul

I’m struck by the extent to which Christopher Nolan’s celebrated Dark Knight trilogy (of which the monumental second chapter, The Dark Knight, was released 10 years ago this week), watched back to back, can be fruitfully considered as an extended comic-book riff on the story of Abraham and God’s judgment on Sodom in the Book of Genesis.

“God saved my life”: The Rider star Brady Jandreau

Brady Jandreau is a young Lakota Sioux rodeo star who met filmmaker Chloé Zhao while she was filming at a South Dakota ranch.… Zhao wanted her next film to be about Jandreau’s world and way of life. While she was searching for a way into the story, Jandreau’s career came to an abrupt end when a bronco threw him and then stomped on his head, shattering his skull.

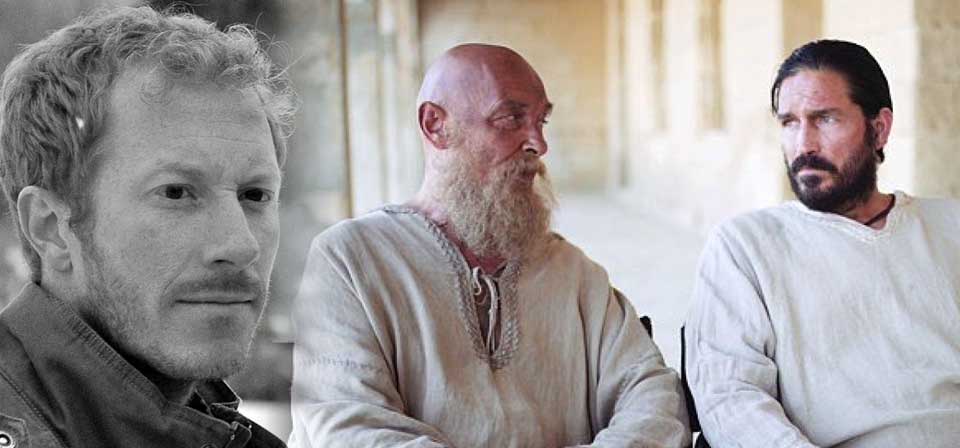

Interview: Paul, Apostle of Christ Writer–Director Andrew Hyatt

The Full of Grace filmmaker talks about the challenges of bringing Scripture to life and the problems with many faith-based films.

The seductive distortions of Call Me By Your Name (2017)

If you didn’t know that the Best Picture–nominated Call Me By Your Name is an uncritically rapturous celebration of a same-sex relationship between an inexperienced youth played by Timothée Chalamet and an experienced man played by Armie Hammer, you might almost guess it from the opening titles, an arty overture for the film that follows.

2017: The year in reviews

American moviegoers aren’t necessarily the most demanding viewers in the world, but it seems we have our limits, if dire movie-ticket sales for 2017 are any indication.

Interview: Catholic filmmaker Timothy Reckart, director of The Star

Timothy Reckart is the talented creator of one of the most original and memorable animated shorts in recent years, the 2012 Oscar-nominated stop-motion gem “Head Over Heels.” He is also a devout Catholic working in Hollywood.

What does a starship need with God?

“What does God need with a starship?” That line, uttered by William Shatner’s Capt. James T. Kirk in the much-derided Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (1989) — co-written and directed by Shatner himself — is probably that film’s most famous (or infamous) moment.

An inherited nightmare: Watching the Puritan horror of The Witch with Catholic eyes

What is most unsettling about The Witch is not the manifest presence of the Devil and the malevolence of his minions, but the seeming absence of God and the impotence of the family’s faith and prayers.

Reinventing the Vault: Disney’s classy new remakes

Linking these three terrific family films is a defiantly old-fashioned, almost countercultural lack of ironic revisionism and gritty edginess. Each of them feels in some way like a kind of movie they don’t make any more — if they ever did.

Apostasy, ambiguity and Silence

Shusaku Endo’s 1966 novel Silence honors 17th-century Japanese martyrs who sang hymns as they succumbed slowly to grueling deaths. But it also empathizes with, perhaps even exonerates, many who capitulated to official demands for ritual renunciations of Christian faith — typically trampling on images of Jesus or Mary, called fumie, designated for this purpose.

2016: The year in reviews

In a sense every year is a good film year, but some years you have to go further afield than others.

Religion and rootlessness in 2016 movies

The many faces of Jesus at the movies in 2016 were perhaps the most notable trend in a larger pattern of notable religious themes in the year’s films. There were, though, other trends last year worth noting.

The many faces of Jesus at the movies in 2016

I can’t think of another year quite like 2016. To begin with, Jesus himself was on the big screen in an extraordinary number of screen incarnations.

What we lose when Star Wars goes to the Dark Side

Even features come with trade-offs, and the Marvelization of Star Wars is no exception. This might not be as clear in The Force Awakens — about as pure a work of nostalgia and homage as can possibly be contrived short of a shot-for-shot remake — as it is in Rogue One, where the Marvel-style engineering is more obvious.

Junior Knows Best: We need to talk about cartoon parents

I don’t expect animated heroes to have uniformly ideal, harmonious family lives. It’s not realistic — and it doesn’t make for good drama, which needs conflict. The ubiquity of the pattern, though, is striking.

Doctor Strange and Hacksaw Ridge: Breaking rules and the greater good

In each of their latest films, the battle against a threatening power raises questions about which principles the protagonist should or shouldn’t compromise in order to protect his world — questions that aren’t necessarily clearly answered by the end of the film.

Hacksaw Ridge: Mel Gibson and Robert Schenkkan at the Sheen Center

The director and screenwriter spoke at a screening of the film at the New York Archdiocese’s cultural center, and I chatted with Gibson about the film.

The Greater Freedom: Karol Wojtyla and Our God’s Brother

As a seminarian in the 1940s, the future Pope St. John Paul II wrote a play about a Polish artist turned religious who helped inspire his vocation. In 1997, a film adaptation featuring Christoph Waltz was directed by Krzysztof Zanussi (Life for Life).

Recent

- Crisis of meaning, part 3: What lies beyond the Spider-Verse?

- Crisis of meaning, part 2: The lie at the end of the MCU multiverse

- Crisis of Meaning on Infinite Earths, part 1: The multiverse and superhero movies

- Two things I wish George Miller had done differently in Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga

- Furiosa tells the story of a world (almost) without hope

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.