Articles

A deep cut: The Green Knight

After the library of books that is the Bible, no literary corpus means more to me than Arthuriana, and no Arthurian work means more to me than Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

Interview: The Chosen producer Derral Eves

Part of the success story behind writer-director Dallas Jenkins’ popular life-of-Jesus TV series is the remarkable crowdfunding approach spearheaded by viral marketing strategist Derral Eves.

Of Animals and Men: Extraordinary story, mixed presentation (2019)

Of Animals and Men tells a story of light shining in the darkness — but the preciousness of the light depends in a way on the prevalence of the darkness, and, in that connection, it must not be forgotten that the Nazis were not the sole agents of darkness.

A Triduum ritual: The Miracle Maker

Our seasonal movie-watching during Advent, Lent, and the Christmas and Easter seasons varies from year to year, but Triduum is always the same.

Christopher Plummer, the cross, and the swastika

“That damn movie follows me around like an albatross,” Christopher Plummer once fumed about the one film for which — despite a prolific, varied, successful career in film, television, and theater — he would always be best known.

SDG’s top films, 2000 – 2020

21 years. That’s how long I’ve been at this. A film list 21 years in the making. 21 top films. 21 runners-up. 21 honorable mentions.

Filming Fátima: Interview With Filmmaker Marco Pontecorvo

The cowriter and director of a new film about Our Lady of Fátima talks about why he was drawn to the story and how he tried to realize the miraculous, from a very human Virgin Mary to surreal visions of war and hell.

AKA Jane Roe: Unraveling the complicated life of Norma McCorvey (2020)

The FX documentary asks hard questions of both sides of the abortion debate — but only one side gets thoughtful answers

In search of true confession in the movies

Of the seven sacraments at the heart of the Church’s life, from the very beginning perhaps the most intriguing to filmmakers has been, ironically, the least visually impressive — a hidden rite involving only the minister and the recipient.

Sight & Sound Theatre’s Jesus: An Evangelical Gospel story

“Where the Bible comes to life” is the slogan of Sight & Sound Theatres, headquartered in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in the heart of Amish country.

Coronavirus Quarantine Streaming Options for Lent and Easter (and More)

In the last few weeks, articles about movies to stream while sheltering in place during your coronavirus quarantine have proliferated across the internet almost as fast as the virus has spread around the world. What makes this article different?

2019: The year in reviews

An exquisite art-house film about a beatified martyr. The triumphant arrival of a belated documentary of a celebrated gospel concert. A fact-based drama about an alliance of devout and unbelieving survivors of clerical sex abuse calling for justice. These are just a few of an unusually large crop of notable films that tackled religious and spiritual themes in 2019.

Faith and Ferocity: Interview With Harriet Producer Debra Martin Chase

Harriet’s appeal is multifaceted, appealing to three demographics underserved by mainstream Hollywood fare: women, people of color and people of faith. Producer Debra Martin Chase knows something about these three demographics.

Of grief and ghosts: Interview with Light from Light witer-director Paul Harrill

Silence, reflection, the search for meaning, the interior life: These are among the hallmarks of Paul Harrill’s work.

‘Conquerors of the moon’: Documentaries commemorating the Apollo project

“Honor, greetings and blessings to you, conquerors of the moon, pale lamp of our nights and our dreams!” Paul VI exclaimed in his July 21 message to the astronauts on the day after the lunar landing. “Bring to it, with your living presence, the voice of the spirit, the hymn to God, our Creator and our Father.”

Franco Zeffirelli’s complicated, Catholic life: What does it mean for his art?

For Catholics and other Christians, the contradiction between Zeffirelli’s faith and the themes of his religious films on the one hand and his openly homosexual lifestyle on the other raise perennial questions about the mysterious relationship of art and the artist.

Emanuel: Racial violence and Christian forgiveness

Forgiveness in the face of murderous violence is a radical act that remains as shocking and controversial today as it was when a Second Temple–era Palestinian prophet commanded his disciples to love and to pray for those who persecuted them and ended his mortal life praying for divine forgiveness for his own executioners.

The secular apocalypse: Irreligion, pop culture, and the end of the world

All art — even pop art, even bad or offensive art — is in some way a mirror to the soul of the culture that created it. Whether we embrace them, condemn them, or are indifferent to them, these secular apocalypses reveal something about who we are as a culture.

‘The Redemption Project’: Convicts, Victims, Confrontation and Forgiveness

The prison setting and the word “redemption” in the Ludlumesque title are vaguely evocative of the most popular prison movie of all time, The Shawshank Redemption. A prison sentence, though, is seldom a redemptive experience for anyone.

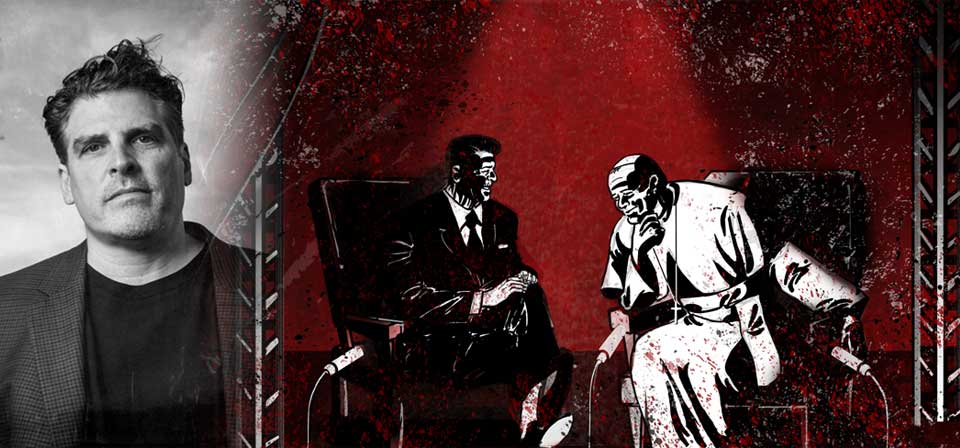

Pope John Paul II, Ronald Reagan and The Divine Plan: Filmmaker Robert Orlando (Interview)

Anyone who directs a movie about the converging efforts of Pope St. John Paul II and Ronald Reagan to take on the Soviet Union is someone I’m interested in talking to. But Robert Orlando isn’t just anyone to me.

Recent

- Crisis of meaning, part 3: What lies beyond the Spider-Verse?

- Crisis of meaning, part 2: The lie at the end of the MCU multiverse

- Crisis of Meaning on Infinite Earths, part 1: The multiverse and superhero movies

- Two things I wish George Miller had done differently in Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga

- Furiosa tells the story of a world (almost) without hope

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.