Articles

The theology and philosophy of Avengers: Age of Ultron

We aren’t exactly talking The Matrix here, but it’s been awhile since a Hollywood popcorn action movie elicited such a range of theological and philosophical analysis.

“Franciscan” movies for Pope Francis’ US visit

Much like Pope Francis himself at times — or even like Jesus himself — Saint Francis of Assisi has often been made into an avatar or mascot of people’s likes (or dislikes) rather than being recognized as the surprising, vibrant figure he really was.

How James Bond lost his soul: Casino Royale

Casino is more than a reboot: It’s also a kind of origin story, based on the first Ian Fleming novel. As such, it’s the story of how James Bond lost his soul, or whatever was left of it, at the very moment when he dared to hope for redemption.

The taking of an oath: Marriage, annulments, Kim Davis, and A Man for All Seasons

The name of Saint Thomas More has cropped up in recent discussion of current events as never since — well, if not since the English Reformation, at any rate probably since one of my all-time favorite films, A Man for All Seasons, won six Academy Awards at the 1966 Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Director (Fred Zinnemann), and Best Actor (Paul Scofield).

“Brother Ass” or “stupid apes”? Transhumanism, the Imago Dei and Hollywood

As technology progresses and the culture and the Gospel continue to draw further apart, transhumanist aspirations flourish, both as a worldview and in the world of popular culture.

Gun culture and Hollywood: Turning away from violence

All violence is not the same. There are obvious, important differences between realistic war violence, violence in a serious social drama, cartoon violence in an action movie, horrific violence in a crime movie, slapstick violence in a comedy and so forth. Ultimately, though, I think it’s important to give ourselves regular breaks from violence of any kind. Violence is unavoidably part of human nature, but it’s far from the most interesting part.

The spiritually aware cinema of Jean‑Pierre and Luc Dardenne

The Dardennes’ films generally have redemptive arcs of some sort, or at least the hope of redemption — though there are no traditional happy endings, only hopeful new beginnings. Theologians ponder the mystery of evil; the Dardennes are intrigued by the mystery of goodness.

The Train: When is art worth dying for?

Are manmade things ever worth dying for? How do you weigh the value of art or artifacts against the value of human life? On the one hand, human life is sacred; things are just things. On the other, the cultural heritage of a people is an irreplaceable treasure that belongs not only to the whole community, but to all future generations.

“We are not things”: Mad Max: Fury Road and commodifying human life

In another movie, a line like “We are not things” could be a platitude, but in the context of vividly imagined atrocities with unnerving echoes of recent headlines, this simple affirmation is fraught with topical power that has only grown in the months since the film’s theatrical debut.

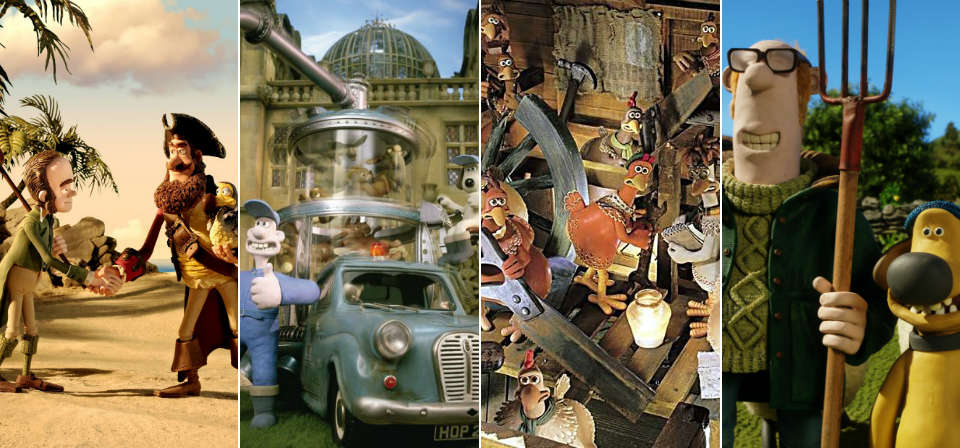

Shaun the Sheep and beyond: The magic of Aardman

For the Aardman filmmakers, it seems that inspiration and the tactile work of stop-motion go hand in hand.

The greatest American films: Film critics vs. the Vatican

One much-noted point about the BBC list is how few Academy Award Best Picture winners made the list. Naturally, I’m interested in a different comparison: How does the BBC list compare to the 1995 Vatican film list?

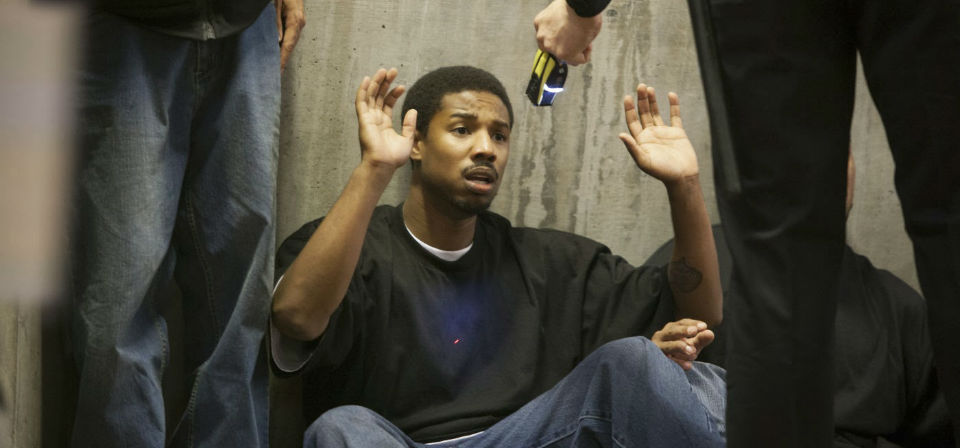

Black lives matter: Watching Fruitvale Station one year after Eric Garner

I recently rewatched Fruitvale Station (2013), first-time director Ryan Coogler’s shattering Sundance winner, with my oldest son, who has since gotten his driver’s license. Some day he will face that inevitable first traffic stop, and I want him to be aware just how different that encounter will be for him, with his bleached complexion and shining towheaded crown, than for many young men in the minority neighborhoods all around us.

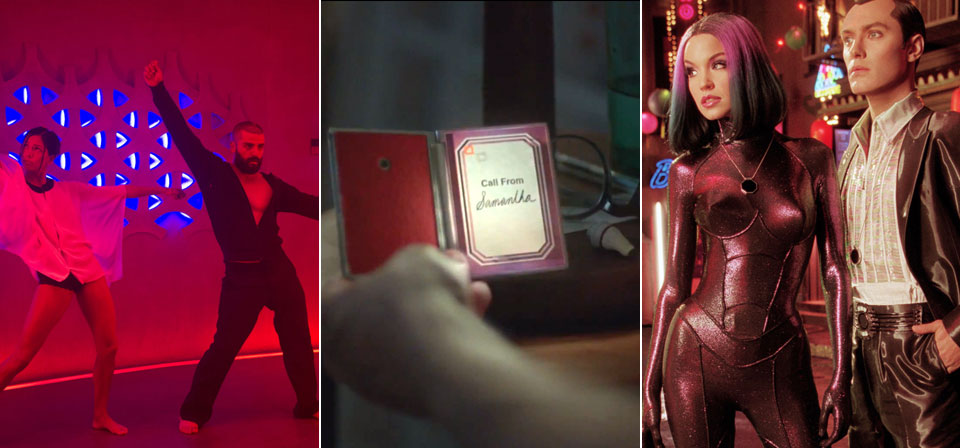

Computer dating: Artificial intelligence and robot sex in Ex Machina and Her

Alex Garland’s Ex Machina is the latest in a string of recent science-fiction films exploring questions around artificial intelligence, transhumanism and the role of technology in our lives.

A Catholic family summer vacation entertainment survival guide

As a Catholic film critic, one of the top questions I get from parents during the summer months — right after “What’s good in theaters in this summer?” — is “Do you know anyone who does what you do, but for television?”

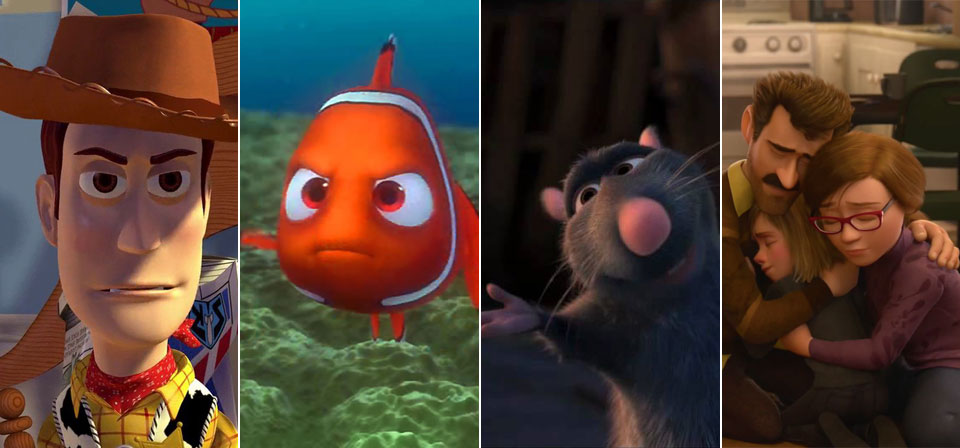

What’s so special about Pixar’s flawed protagonists and their moral journeys

Only Pixar regularly impresses on viewers that just because you’re the hero of your story doesn’t mean you’re right about everything: that you may make serious mistakes, there may be consequences, and you must take responsibility.

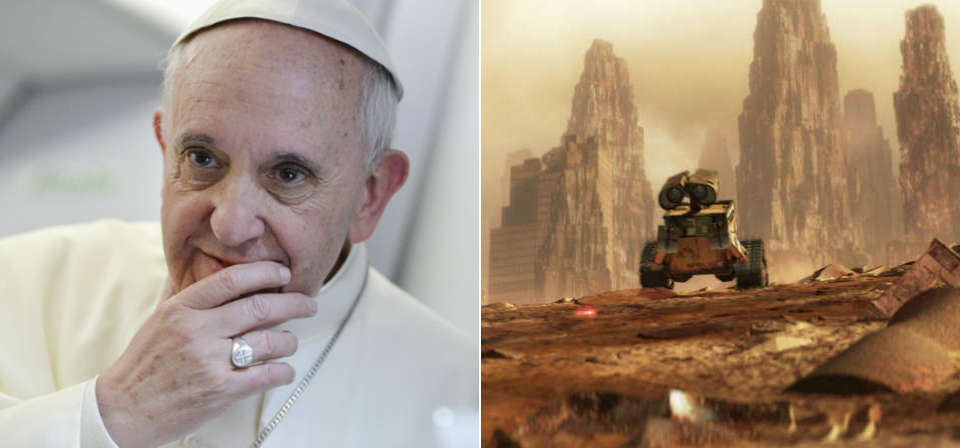

Pixar and the Pope: Pope Francis’ Laudato Si’ and Pixar’s Wall-E

“The earth, our home, is beginning to look more and more like an immense pile of filth,” Pope Francis writes. “In many parts of the planet, the elderly lament that once beautiful landscapes are now covered with rubbish” (LS 21). From the outset Wall-E looks as if it had been created with these words in mind, projecting them into a dystopian future in which rubbish has expanded to cover the entire planet, even surrounding the Earth in a halo of space debris.

The extraordinary career of Christopher Lee

Sir Christopher Lee, who died on June 7 at the age of 93, had an extraordinary career and an extraordinary life. To speak only of his film work, while it’s impossible to sum up his incredibly prolific and varied output — IMDb.com credits him with more than 280 acting roles over a nearly 70-year career — Lee’s lean, towering build (he stood five inches over six feet) and sonorous baritone voice were well suited to playing villains and monsters.

Roman holidays: Visiting the Eternal City in the movies, from the sublime to the ridiculous

You could almost watch Bicycle Thieves and Roman Holiday back to back and never realize they were shot in the same city only five years apart.

Becoming Saint Óscar Romero

The recent beatification of Óscar Romero, Archbishop of San Salvador from 1977 until his assassination in 1980, has drawn new attention to the gap between public perception and reality regarding this popular but controverted figure in El Salvador’s turbulent history. For those interested in beginning to understand who Blessed Archbishop Romero really was, the Christopher Award–winning 1989 film Romero, starring Raúl Juliá, isn’t a bad place to start.

The dangerous family films of Brad Bird

Few filmmakers working in Hollywood today enjoy so sterling a reputation as Bird. Although Tomorrowland is only his fifth feature film, and only his second in live action, his achievements in his first four films are extraordinary.

Recent

- Crisis of meaning, part 3: What lies beyond the Spider-Verse?

- Crisis of meaning, part 2: The lie at the end of the MCU multiverse

- Crisis of Meaning on Infinite Earths, part 1: The multiverse and superhero movies

- Two things I wish George Miller had done differently in Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga

- Furiosa tells the story of a world (almost) without hope

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.