Articles

Exodus: Gods and Kings: Theological reflections

It’s a movie with many problems, like most of Scott’s recent epics (Prometheus, Robin Hood, Kingdom of Heaven), but Scott has a better story to work with here and adds something of value to the world of Bible cinema.

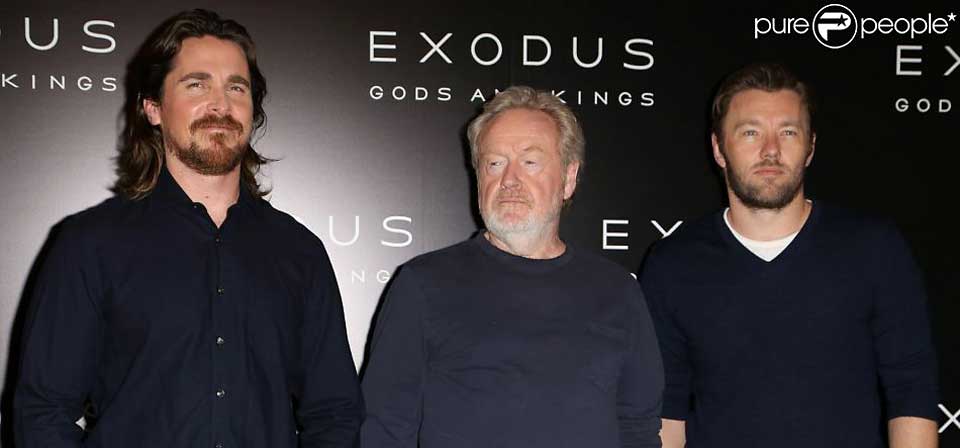

Interview: Exodus: Gods and Kings filmmakers Ridley Scott, Christian Bale and Joel Edgerton

Ridley Scott’s Exodus: Gods and Kings (in theaters Dec. 12) is the year’s second major Old Testament epic from a director who is not a believer — but don’t get Scott started on Noah’s rock-monster Watchers.

Moses at the movies

The Exodus is probably the Bible’s most cinema-ready story, the perfect Bible-movie subject. Unlike the stories of Noah, Abraham, David, Jesus, Peter, or Paul, it offers a sustained narrative structure, with a clear central conflict between a strong hero and a strong villain, building to a series of grand climaxes.

How Disney’s Maleficent subverts the Christian symbolism of Sleeping Beauty

Give me princesses like Leia from Star Wars, Merida from Brave or Tiana from The Princess and the Frog any day. But there’s a difference between creative revisionism and simple inversion.

Dystopia, The Hunger Games and the critique of the culture of death

The word utopia was coined by St. Thomas More in his book of that name — an important and enigmatic work of fiction and political philosophy generally understood as some sort of satire.

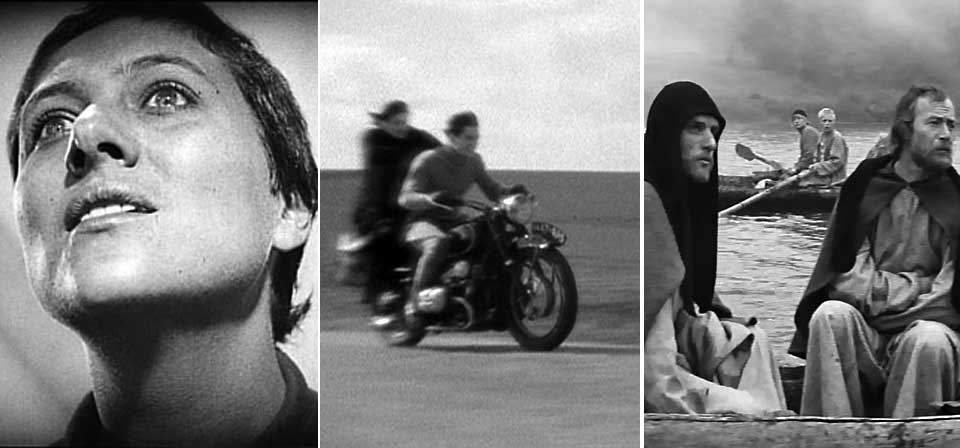

Seeking accessible saint movies … for less arty viewers

A reader writes: “I am looking for easy-to-approach religious movies, especially ones on saints. Intellectually challenging, subtitled, confusingly artistic movies seem to dominate. While I really love those types of movies, I am trying to find films for my Bible study group … We tried the first half of Diary of a Country Priest, and I worried one might try to smother herself with my sofa pillow to end her misery. Do you have any thoughts?”

Taking themselves lightly: “The Flying Nun” and The Reluctant Saint

If “The Flying Nun” is a bit too, well, flighty for some tastes, consider another 1960s production about a consecrated religious — a real-life one in this case, and a canonized saint — given to slipping the surly bonds of earth.

Religious filmmakers explore — and cross-examine — faith

Strikingly, where the religious films of nonbelievers often feature idealized religious characters more or less certain in their faith, films by believers often put their religious characters’ faith to a more existential test.

Do atheists and agnostics make the best religious films?

One of the noblest functions of art is the invitation to empathy: an invitation extended not only to the audience, but also to the artist.

From the Crusades to Columbus: Religion in Ridley Scott’s Historical Epics

A self-described atheist, Sir Ridley Scott has developed a generally bleak vision of religion, particularly the Judeo-Christian tradition, throughout his work, above all in historical sagas like Robin Hood (2010) and 1492: Conquest of Paradise (1992).

Two Very Different Responses to Parenthood: Chef and Obvious Child

Among this summer’s successful indies were a pair of R-rated comedies — each from a filmmaker serving as writer, director and star — depicting two very different responses to the formidable responsibilities of parenthood.

Jewish/Catholic: Religious Identity, Fluidity and the Holocaust

“One is Christian or Jewish, not both.” So says the chief rabbi of Paris in The Jewish Cardinal (2013), Israeli-born filmmaker Ilan Duran Cohen’s biopic about Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger (Laurent Lucas) — a Jewish convert to Catholicism who insisted on religious dual citizenship, embracing Catholicism without rejecting Judaism.

Stop-Motion Macabre

Stop-motion animation — which, unlike computer animation and traditional hand-drawn cel animation, utilizes real objects shot frame by frame, with tiny adjustments made between shots — is a defiantly old-fashioned, niche medium, often used to creepy effect: Henry Selick’s The Nightmare Before Christmas and Coraline; Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride and Frankenweenie; Aardman’s Wallace and Gromit: Curse of the Were-Rabbit.

BBC’s amiable, nostalgic ‘Father Brown’ doesn’t keep faith with Chesterton

“I like detective stories,” G. K. Chesterton once wrote; “I read them, I write them; but I do not believe them.” Chesterton put into his beloved Father Brown stories a great deal that he did not believe — exotic crimes, improbable methods, wiredrawn detective work — but also a great deal that he did believe, much of it on the lips of his moon-faced clerical sleuth.

Superhero movies and Catholic faith

Less than two months ago, the British Catholic writer Stratford Caldecott died after a lengthy battle with cancer. In the weeks prior to his death, his name became improbably entangled in a viral Twitter storm that made international news in connection with the superhero movie Captain America: The Winter Soldier, now available on home video.

Hollywood After September 11, 2001

The shadow of September 11, 2001 over Hollywood still lingers.

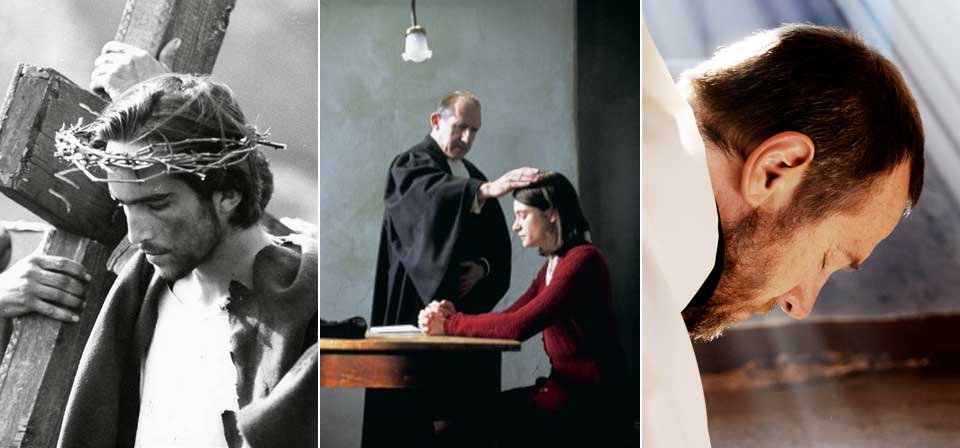

A haunting film about the “martyr of Auschwitz”

Nearly two decades before his Oscar-winning role as a Jew-hunting Nazi in Quentin Tarantino’s lurid WWII fantasy Inglourious Basterds, Christoph Waltz played an Auschwitz survivor whose escape is linked to the death of one of Auschwitz’s most celebrated victims, St. Maximilian Kolbe.

Auf Wiedersehen! Stay tuned!

It was a busy summer season; it wasn’t a terribly good summer season — above all for family audiences, who were left almost completely out in the cold. Still, it was generally an improvement on last summer, particularly for popcorn spectacle and action.

Life for Life: Maximilian Kolbe, martyr of Auschwitz (1991)

Two great mysteries hover over the cardinal moment in St. Maximilian Kolbe’s life, a quiet exchange of words with the deputy camp commander at Auschwitz-Birkenau heard by few and lasting probably less than a minute.

Robin Williams RIP

In the flood of commentary and sorrow surrounding the death of Robin Williams, apparently by suicide, so many are struggling over what to say about a man who seemed never to be at a loss for words.

Recent

- Crisis of meaning, part 3: What lies beyond the Spider-Verse?

- Crisis of meaning, part 2: The lie at the end of the MCU multiverse

- Crisis of Meaning on Infinite Earths, part 1: The multiverse and superhero movies

- Two things I wish George Miller had done differently in Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga

- Furiosa tells the story of a world (almost) without hope

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.