Romero (1989)

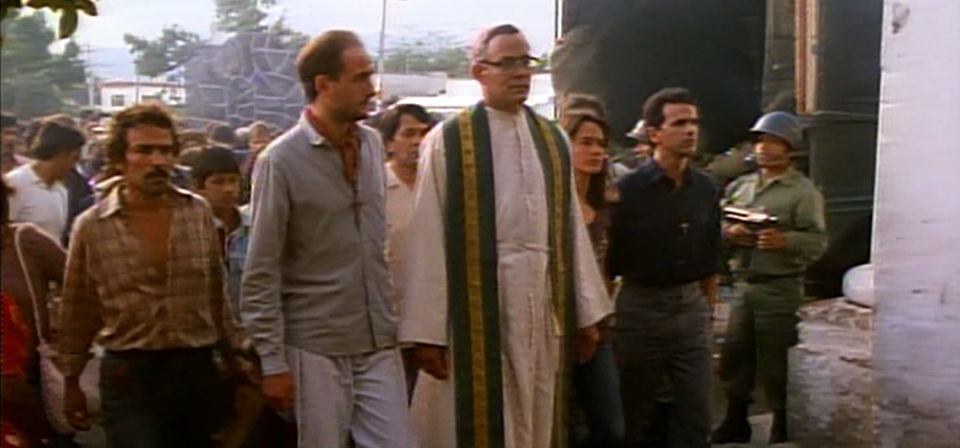

“A good compromise choice” is how one observer describes the 1977 appointment of Oscar Romero (Raul Julia) — a conservative, orthodox, apolitical bishop of a small rural diocese — to the archbishopric of San Salvador, the highest ecclesiastical office in El Salvador.

By the time Archbishop Romero’s tempestuous three-year tenure comes to its violent end, “compromise” is a word no one will ever again think of in connection with him.

Caveat Spectator

Graphic depictions of murder and massacre by gunfire; sometimes bloody or mutilated photographs of torture victims; offscreen and implied torture; a brief depiction of a nude corpse; a single coarse metaphor; two incidents of desecration of the Eucharist.The first feature film from the Paulist Fathers’ moviemaking division, John Duigan’s Romero tells the true story of Latin America’s best-known and most revered modern martyr, Oscar Arnulfo Romero y Goldamez, a man whom John Paul II described as a "zealous pastor who gave his life for his flock," and at whose tomb in San Salvador Pope John Paul II has prayed when visiting El Salvador.

Where Romero excels as a film is in its depiction of its subject’s gradual transformation. Like Richard Burton in Becket, Raul Julia’s Romero is a man morally transformed by office and responsibility. Yet whereas Becket becomes a new man virtually overnight, Romero goes through a more organic, gradual process, responding to specific crises.

Romero comes to the archbishopric at a time when El Salvador is torn apart by violence and injustice. El Salvadoran military forces — aided and equipped by the United States as a defense against Communism — oppose the country’s Marxist guerrilla resistance. However, much of what is done in the name of "fighting Communists" is really just repressing the poor, or anyone who speaks out on their behalf.

As played by Julia, Romero seems at first a man singularly unsuited for high office, particularly in such a time of crisis. By nature timid, bookish, and retiring, he has no presence, no political instincts, no sense of moral authority. He doesn’t even have a decent pair of shoes.

He does, however, have one important virtue in the eyes of El Salvador’s wealthy European oligarchy, military controllers, and complacent bishops: He’s uncontroversial. At least he’s not on the side of the country’s guerrilla resistance movement, and that’s good enough for the ruling classes. Certainly they’re sure he’s a man who won’t rock the boat.

What no one anticipates — including Romero himself — is how he will respond when someone else rocks the boat. Less than a month into his office, demonstrators in the main plaza of San Salvador are surrounded by police forces, and some are killed. Days later, Romero is stunned when a popular priest friend of his known for advocacy of reform and social justice is assassinated, along with an old man and a young boy accompanying him to Mass.

Romero’s response to this atrocity — presumably the work of a military death squad — is a dramatic proposal: Cancel all Sunday Masses that week throughout the archdiocese except for a single memorial Mass at the cathedral, to unite the faithful in this time of crisis.

The proposal meets with resistance from other bishops. "It will be interpreted as a political statement," one protests. Romero, a reasonable man, feels the weight of this objection; yet in the end he grasps that the decision must be his. The Masses are canceled.

Slowly, the archbishop is revealed as a man of growing courage. At times he exhibits physical bravery, as when he climbs into a van with armed and masked thugs, or refuses to be intimidated by the guns of a hostile military force occupying a parish church.

But other, quieter acts require a form of courage as well. Told that his appointment with the fraudulently declared president-elect must be rescheduled, Romero unflinchingly replies, "I will wait," and makes himself comfortable in the waiting room. On a subsequent occasion, he strides into the president’s office unannounced, and refuses to be satisfied with political niceties. He doesn’t even shy from calling the president (also named Romero, coincidentally) a liar to his face.

The archbishop’s moral crusade earns him enemies, not only among the ruling alliance of military powers and aristocracy, but on two other fronts as well: the Marxist resistance movement, and even some of his fellow priests and bishops who fear the wrath of the establishment, and even accuse Romero being a Marxist himself.

Romero repudiates Marxism, but will not allow anti-Marxism to be used as a weapon to quell moral criticism. He preaches a theology of liberation, but a liberation "rooted in faith" that is "so often misunderstood" in merely political terms.

Like Roland Joffé’s The Mission, Romero raises the issue of "liberation theology," but rejects what is unacceptable in some forms of that school of thought: class warfare, guerrilla tactics, priests taking up arms. Certainly the film has no sympathy for the Marxist resistance, which it depicts as brutally lawless.

Even so, Romero’s real opposition comes not from the guerrillas, but from El Salvador’s controllers — especially the military, which ultimately overthrows the fraudulent presidency and establishes a series of military juntas operating with continued U.S. support.

Unfortunately for the film, none of Romero’s enemies, even among the military, emerges as a knowable or compelling character. Eddie Velez plays a callous officer who opposes Romero at several turns, and the archbishop also has a couple of run-ins with members of the aristocracy as well as the fraudulently elected president; but the film has no true antagonist.

This weakens the drama, and is Romero’s main flaw as a film. In Becket, the title character had Henry II to push against; in A Man for All Seasons, Sir Thomas had Henry VIII (not to mention Cromwell, Wolsey, Norfolk, Cranmer, and finally, in the Tower, even his own beloved wife and daughter). It was this lively opposition that made these dramas compelling on a personal level.

In Romero, by contrast, the dramatic conflict is shifted within; instead of Man against Man, it is Man against Himself. It’s a credit to the strength of Raul Julia’s performance — perhaps a career high point — that Romero’s inner struggle and outward transformation from timid academic into thundering prophet is so compelling in itself. It’s a four-star performance in a three-star film.

The film is also strengthened by its use of Romero’s actual words from recorded homilies, interviews, and speeches. Romero turned out to be a powerful speaker, and all over the country people eagerly tuned in every Sunday to hear his broadcast homilies. In the film, we hear Romero call upon U.S. President Jimmy Carter to stop providing El Salvador with military support that was only being used to oppress the people (a call that was rejected). We hear him reach out to the soldiers themselves:

No soldier is obliged to obey an order contrary to the law of God. No one has to obey an immoral law. It is high time you obeyed your consciences rather than sinful orders. The church cannot remain silent before such an abomination… In the name of God, in the name of this suffering people whose cry rises to heaven more loudly each day, I implore you, I beg you, I order you: Stop the repression!

The day after delivering that speech, Oscar Romero was assassinated. Soon afterward, El Salvador descended into a decade-long civil war that claimed the lives of upward of 60,000 El Salvadorans.

Archbishop Romero was killed in the very act of offering the sacrifice of the Mass, almost in the act of elevating the Eucharistic elements. Simply by portraying this event essentially as it happened, Romero presents the archbishop’s life and death as a sacrifice in union with the sacrifice of Christ.

This final sacrifice is foreshadowed by other Masses offered under threatening or difficult circumstances. The Mass, we see, is a bold and radical act, even in a way a revolutionary act: for in the Mass Jesus is with us and in us. The Mass is the fullest earthly expression of that divine solidarity with which the Lord himself challenged one of the church’s earliest oppressors: "Why are you persecuting me?"

It’s a question that continues to apply to all who persecute God’s children anywhere in the world.

Note: Some viewers used to the American custom of using the honorific "monsignor" only for specially honored priests may be thrown by references in the film to Romero as "Monsignor" both before and after his appointment as archbishop, but in Latin America the honorific extends also to bishops. Romero is a bishop (not just a "monsignor") at the time of his election to the archbishopric.

Related

Becoming Saint Óscar Romero

The recent beatification of Óscar Romero, Archbishop of San Salvador from 1977 until his assassination in 1980, has drawn new attention to the gap between public perception and reality regarding this popular but controverted figure in El Salvador’s turbulent history. For those interested in beginning to understand who Blessed Archbishop Romero really was, the Christopher Award–winning 1989 film Romero, starring Raúl Juliá, isn’t a bad place to start.

RE: Romero

Link to this itemI just found out about your website, and thought of it good because of the reference from Catholic.net. However, I am disappointed, and are doubtful now of your recommendations, after reading what you wrote about the movie Romero:

The first feature film from the Paulist Fathers’ moviemaking division, John Duigan’s Romero tells the true story of Latin America’s best-known and most revered modern martyr, Oscar Arnulfo Romero y Goldamez, a man whom John Paul II described as a ”zealous pastor who gave his life for his flock,” and at whose tomb in San Salvador the Holy Father has prayed when visiting El Salvador.”I am a Salvadorean. I hear Msgr. Romero’s homilies. Many Catholics stopped practicing our religion because of Msgr. Romero’s homilies. I remember once, he gave Mass at my school, and he OKed taking arms in order to help the poor. I felt terrible for not doing so. Being a teenager, and coming from a Priest, my mind and heart told me killing for a greater good could not be good. His interpretation of some passages of the Bible were horrible. As an adult now, I realize how theologically wrong they were.

I have formed myself… found my way back to Church… but many others in El Salvador, including close members of my family, have totally lost trust in the Church. I think Msgr. Romero did more harm than good. Definitely, “an eye for an eye” is not the pedagogy of Christ — it was his.

I’m very sorry you recommend the film. Very sorry. If it portrays a kind, generous, gentle man… I knew him. He wasn’t. If it portrays a pastor, caring for his souls… I can tell thanks to him many sheep left the way of the Church… Please keep this message for your website. I hope it helps you.

Recent

- Benoit Blanc goes to church: Mysteries and faith in Wake Up Dead Man

- Are there too many Jesus movies?

- Antidote to the digital revolution: Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality

- “Not I, But God”: Interview with Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality director Tim Moriarty

- Gunn’s Superman is silly and sincere, and that’s good. It could be smarter.

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.