Tags :: Science Fiction

Elio is a space adventure that Toy Story’s Andy would actually enjoy

Pixar’s Elio is the kind of movie that Lightyear should have been.

The Wild Robot (2024)

Watching Chris Sanders’s The Wild Robot, I felt things I haven’t felt in a very long time watching a Hollywood animated movie outside the Spider-Verse: wonder, discovery, joy.

Dune: Part Two exceeds expectations in every way — except humanity

There’s something bracing about a blockbuster epic in 2024 that doesn’t care what you think of it, that is primarily concerned with being the best possible version of itself.

Dune and The Lord of the Rings

In my reviews of Dune: Part One and now Dune: Part Two (filed and pending publication; stay tuned!) I’ve written a bit comparing and contrasting Dune with Star Wars. Here I’d like to consider Star Wars in relation to The Lord of the Rings and J.R.R. Tolkien’s larger legendarium.

Science fiction and transcendence: 2001: A Space Odyssey and the elusiveness of awe

Released 55 years ago, Stanley Kubrick’s iconic masterpiece — honored on the 1995 Vatican film list — has often been likened to “a religious experience.” Why do some of its successors capture this better than others?

Lightyear is an anti–space opera for an anti-heroic age

It pains me to say this: If Lightyear is Andy’s Star Wars, what an impoverished childhood Andy had.

Jurassic World Dominion (2022)

The word “dominion” is uttered once in Jurassic World Dominion, in an oblique, irreverent allusion to Genesis 1. “Not only do we lack dominion over nature, we are subordinate to it,” asserts Dr. Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum) in one of his trademark, smugly iconoclastic epigrams. Later in the same speech, though, Malcolm turns with surprising optimism to the power of genetic science to shape the future. Does he really believe this? Is this speech coherent? Is the film itself coherent?

Dune: Part One (2021)

Watching Dune drove home to me the extent to which no one in 2021 can really go into an adaptation of Dune completely cold.

A Quiet Place Part II (2021)

There are day-to-day crises and traumas that are somehow absorbed into the continuity of our lives, and then there are inexorable turning points that divide our lives into “before” and “after.”

The Mitchells vs. the Machines (2021)

In some ways The Mitchells vs. the Machines harks back to Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs. Most obviously, it’s another goofy, rollicking techno-apocalypse centered on a bumpy parent-child relationship between an awkward, gifted youngster and a handy but technophobic dad.

Ad Astra (2019)

There seems to be no reason for the title Ad Astra, meaning “to the stars,” to be in Latin, except to highlight writer–director James Gray’s elevated intentions.

![The Darkest Minds [video]](/uploads/articles/darkestminds-vid.jpg)

The Darkest Minds [video] (2018)

The Hunger Games’ Rue is now Ruby: Amandla Stenberg takes the spotlight in another YA dystopia that runs its race, but doesn’t diverge enough from its peers to leave anyone hungry for whatever comes next.

Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom (2018)

Apparently velociraptor is the cowbell of dino design and the filmmakers are Christopher Walken.

![A Quiet Place [video]](/uploads/articles/quietplace-vid.jpeg)

A Quiet Place [video] (2018)

It’s funny to think of people scratching their heads when this “quiet” film is justly nominated for sound editing and sound mixing Oscars.

A Quiet Place (2018)

While A Quiet Place is a terrific film just the way it is, I can’t help wishing there were more families like this in other kinds of movies.

Ready Player One (2018)

The sell for Steven Spielberg’s Ready Player One is a little like the sell for Jurassic Park, except instead of dinosaur shock and awe, it’s pop-culture nostalgia shock and awe.

A Wrinkle in Time (2018)

“If it’s bad art,” Madeleine L’Engle once wrote, “it’s bad religion, no matter how pious the subject.”

What does a starship need with God?

“What does God need with a starship?” That line, uttered by William Shatner’s Capt. James T. Kirk in the much-derided Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (1989) — co-written and directed by Shatner himself — is probably that film’s most famous (or infamous) moment.

Alien: Covenant (2017)

To succumb to a regrettable but practically inevitable coinage, Scott wants to make the world of Alien great again — to remind us all what was so terrifying nearly four decades ago about being in space where no one can hear you scream.

Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 (2017)

Here’s the thing: You haven’t even seen Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 yet, but you’re already an incipient fan, aren’t you?

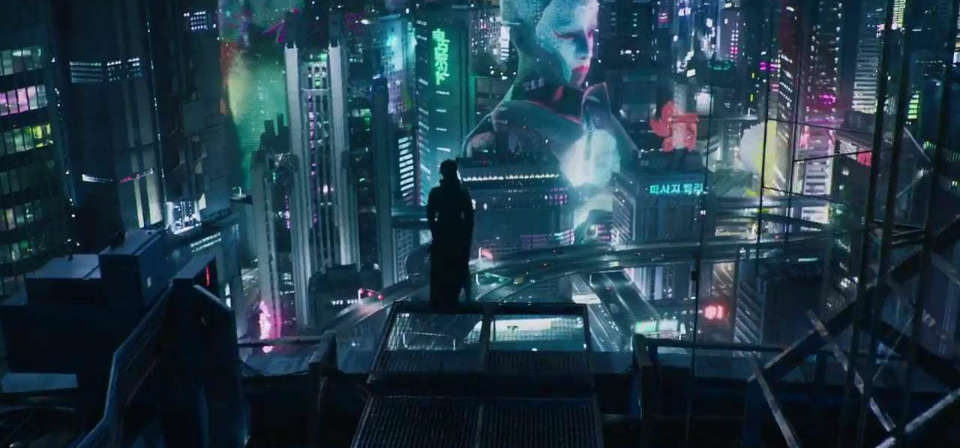

Ghost in the Shell (2017)

Scarlett Johansson is becoming — no, at this point it’s safe to say she is — the default Hollywood poster girl for transhumanism.

Passengers (2016)

If you had to cast two Hollywood actors to watch being all by themselves in a luxury starliner on a doomed 90-year voyage to a planet they will never live to see, you might just pick Chris Pratt and Jennifer Lawrence. In a way, that’s the problem with Passengers, or where the problems begin.

Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016)

All this raises a question: When is a Star Wars movie not a Star Wars movie?

Arrival (2016)

In some ways it warrants comparison with Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, if only because Arrival achieves much of what I was hoping for from Interstellar.

People keep lying about computer “creativity”

Nearly 15 years ago the British futurist Ian Pearson predicted that by 2010 the world’s highest-paid celebrity would be an artificial “synthespian.” That didn’t pan out, but now journalists and PR people are trying to hype A.I. entities as filmmakers behind the camera.

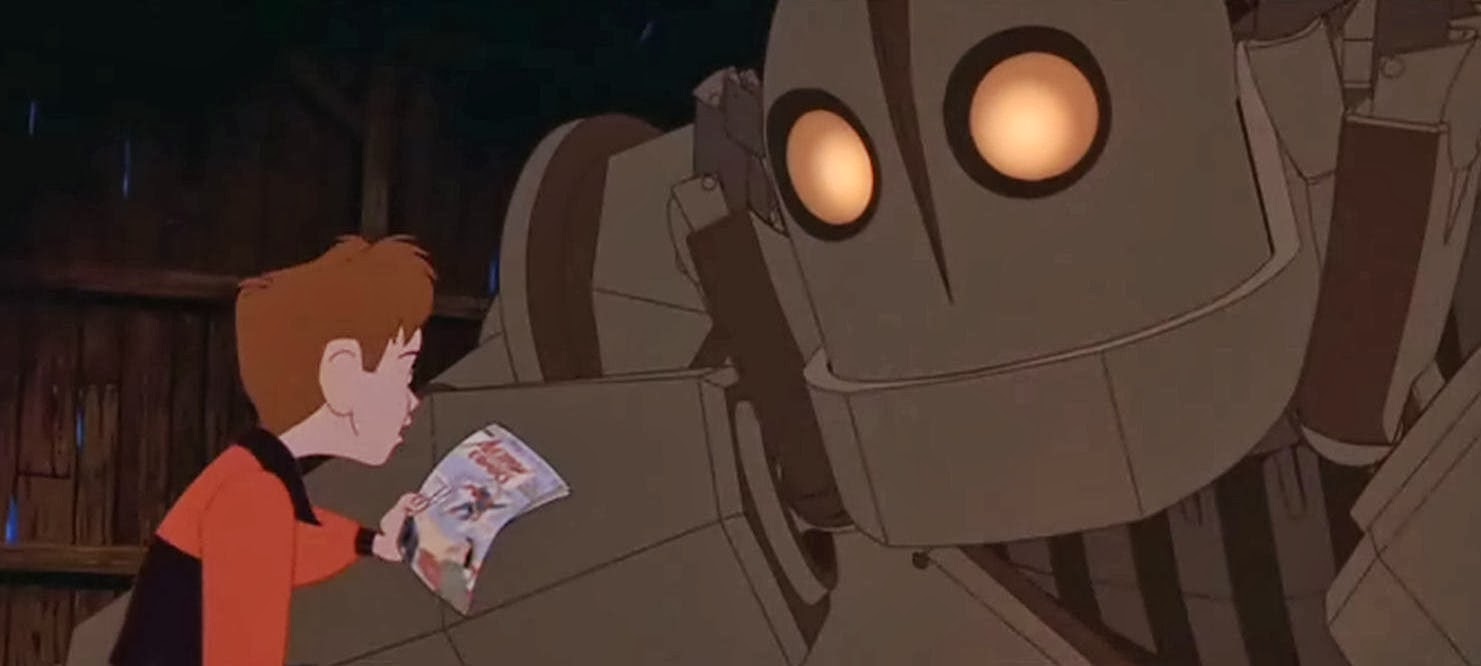

The Iron Giant (1999)

There is a purity to Brad Bird’s directorial debut The Iron Giant, based on the British poet Ted Hughes’ children’s novel The Iron Man, that is inconceivable in the family film landscape of today.

![Independence Day: Resurgence [video]](/uploads/articles/independenceday2.jpg)

Independence Day: Resurgence [video]

We had 20 years to prepare. I would have liked more time.

Star Trek Beyond (2016)

It’s not saying much, but Star Trek Beyond is probably this summer’s most entertaining popcorn film to date.

The myth and magic of Star Wars:

Is it over?

By the most empirical of measures, it doesn’t look like anything can kill Star Wars. From another angle, one could equally ask: At this late date, can anything revive Star Wars?

Star Wars: Episode VII – The Force Awakens (2015)

I smiled and laughed through much of the film. Why don’t I love it more? Why did The Force Awakens make almost no lasting impression on me?

“Brother Ass” or “stupid apes”? Transhumanism, the Imago Dei and Hollywood

As technology progresses and the culture and the Gospel continue to draw further apart, transhumanist aspirations flourish, both as a worldview and in the world of popular culture.

Fantastic Four (2015)

The negative buzz around the new Fantastic Four is so radioactive you could almost expect to develop superpowers just by reading about it. Ah, but that’s old-fashioned talk. In the 1960s radioactivity was mysterious and eldritch, capable of producing all manner of hulks and spider-men and what have you. In the 1950s you could even get godzillas.

Pixels (2015)

The idea of saving the world from alien invaders with classic video-game skills is not without a certain dumb appeal.

Ant-Man (2015)

Three years ago, when Marvel first announced that Ant-Man would be getting his own movie, I tweeted, “I don’t care how much money Avengers makes. The world does not need an Ant-Man movie.” Ant-Man, I felt, was too minor a hero, too obscure and inconsequential — in a word, too small — to warrant the big-screen Marvel movie treatment.

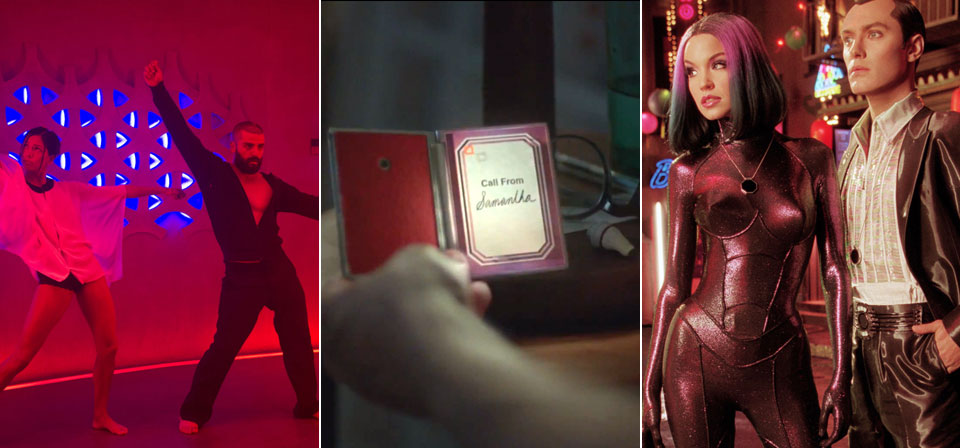

Computer dating: Artificial intelligence and robot sex in Ex Machina and Her

Alex Garland’s Ex Machina is the latest in a string of recent science-fiction films exploring questions around artificial intelligence, transhumanism and the role of technology in our lives.

Jurassic World (2015)

Pratt more than delivers. You could almost say he manages to stand in for Sam Neill, Jeff Goldblum and Laura Dern. He’s got Neill’s toughness, Goldblum’s humor and Dern’s down-to-earthness. His character, Owen Grady, is Jurassic World’s velociraptor trainer, and in a terrific early set piece Pratt persuades me that he’s capable of standing up to three raptors armed with nothing but charisma and nerve.

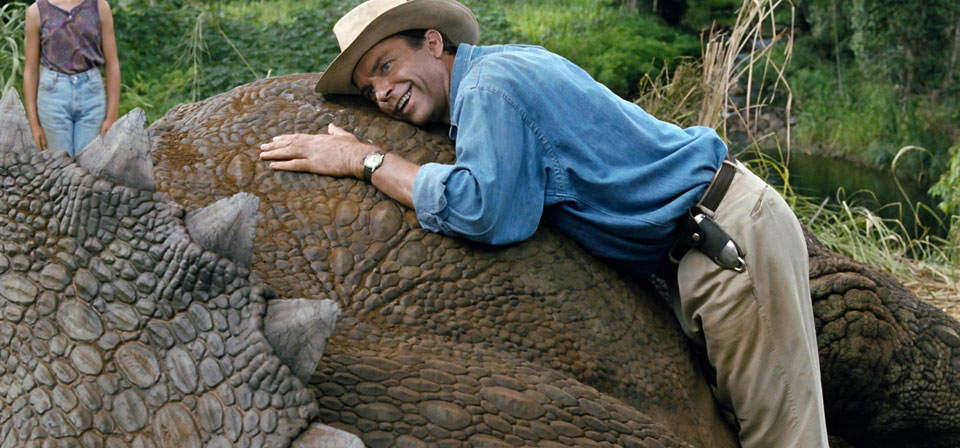

Jurassic Park (1993)

In the twenty-odd years since Jurassic Park pioneered the use of photorealistic computer-animated living creatures integrated into a live-action film, computer animation has become even more prevalent. Yet in all that time, it’s hard to think of a single blockbuster spectacle that uses computer imagery to achieve a similar sense of awe and grandeur.

Tomorrowland (2015)

Tomorrowland argues that the future is as dark or as bright as we choose to make it; that artists, scientists and dreamers can save the world; that the dystopian post-apocalyptic nightmares dominating popular culture are killing us, and are no more inevitable or realistic than the Space-Age techno-optimism of Disney’s Tomorrowland and EPCOT, Roddenberry-era Star Trek and even The Jetsons.

Interstellar and Gravity: Science fiction, outer space and the question of God

Last year’s Interstellar and the previous year’s Gravity follow different paths in a long tradition of asking ultimate questions against the biggest canvas available to our senses, the universe itself.

Why “Star Trek” — and Mr. Spock — matter

The ongoing cultural influence of the “Star Trek” phenomenon is incalculable, and Leonard Nimoy’s contributions are an immense part of that. Nimoy wasn’t just an actor doing a job; in a real sense he was a co-creator who helped to define his character in many ways.

The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 1 [video] (2014)

Katniss Everdeen may be the Mockingjay now, but Jennifer Lawrence is still the girl on fire.

The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 1 (2014)

Propaganda and symbolism have always been a crucial weapon in the arsenal of any campaign, but their value increases exponentially in the information age. This isn’t a particularly radical idea, although this may be the first time it’s trickled down into a blockbuster franchise. Can you imagine Luke Skywalker making subversive videos calling out Darth Vader and coining popular slogans about fighting the Empire?

Interstellar (2014)

If you love art and science, and in particular if you love astrophysics, space travel and movies about them, it will be hard not to love Interstellar. By this I mean not that you will be bound to love it, but that you will take it hard if you don’t. A film like Interstellar is a rare event, and if such a film falls short, it stings in a way that the day-to-day failures of conventional Hollywood fare don’t.

Guardians of the Galaxy (2014)

Guardians is a romp, a lark — rare descriptors for a popcorn summer movie, alas, in these days of dark, grim tentpoles from Maleficent to Hercules, Edge of Tomorrow to Dawn of the Planet of the Apes.

Snowpiercer [video] (2014)

This is the summer’s most thought-provoking action movie.

Guardians of the Galaxy [video] (2014)

If you’re not into turtles, and you have half a brain, this may be the movie for you.

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014)

Wait, where did this movie come from? Dawn of the Planet of the Apes is so not the sequel to Rise of the Planet of the Apes I expected or was prepared for.

Transformers: Age of Extinction [video] (2014)

If Michael Bay can take 165 minutes for his latest Transformers movie, I can take two minutes to review it.

Edge of Tomorrow [video] (2014)

I’m a sucker for a good time-bending movie. This is a good time-bending movie.

Thor: The Dark World [video] (2013)

Is Loki a villain or an antihero? Either way, the fan favorite is basically the Marvel Universe’s answer to Catwoman, but he can’t carry the movie if he isn’t the main antagonist.

Ender’s Game [video]

Orson Scott Card’s classic sci-fi tale emerges from a decade of development hell with its themes and story maybe 50 percent intact — which doesn’t make it a bad film.

Elysium [video]

The director of District 9 is back … with a bigger budget and name stars.

Man of Steel (2013)

To borrow a line from Man of Steel producer Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight: This isn’t the Superman movie we need, but it’s the one we deserve.

Star Trek Into Darkness (2013)

Star Trek Into Darkness outdoes its predecessor in most respects, except creative ambition.

Jurassic Park [video]

Jurassic Park in 60 seconds: my “Reel Faith” review.

Prometheus (2012)

I don’t mind that Prometheus raises big questions without ultimately answering them. Unanswered questions are part of life, and there’s no reason you can’t have them in art. I do mind that Prometheus raises big questions and has virtually nothing interesting, insightful or thoughtful to say about them. If the questions aren’t interesting in this film, why should anyone care whether they’re answered in another one?

Men in Black 3 (2012)

It’s all acceptably diverting, and not actively unpleasant like the 2002 sequel. There are no grand twists or revelations comparable to the truth about the “galaxy” in the original. What the film could most use, I think, is a wide-eyed uninitiate like Linda Fiorentino in the original or Rosario Dawson in the sequel — but one from 1969, which would offer a fresh twist on the outsider’s experience of the MIB’s nutty world.

The Hunger Games (2012)

Suzanne Collins says she got the idea for The Hunger Games while sleepily flicking channels between some reality-show game and footage of the invasion of Iraq until the images began to blur in her mind. What’s bracing about Gary Ross’ film of the first book in Collins’ wildly popular young-adult trilogy is that the topicality of the story’s origins still comes across. When was the last Hollywood science-fiction action blockbuster that felt like actual ideas about the world we live in were at stake?

John Carter [of Mars] (2012)

Burroughs didn’t invent science fiction, but he perhaps created a genre of serial sci-fi fantasy adventure, with an idealized action hero going from one extraterrestrial adventure to another. Carter’s closest literary ancestor may be Sinbad from One Thousand and One Nights, which is saying something. Buck Rogers, James Kirk and Luke Skywalker are all his descendants, and Jake Sully — the hero of Avatar, which really is a patchwork borrowing from everything Burroughs inspired — is perhaps more indebted to John Carter than any other character in history.

Real Steel (2011)

Real Steel is just plain unpleasant to sit through. So much of the movie is spent amid screaming crowds and abrasive music, often in dark, trashy dives, watching giant robots pound each other into scrap metal. The robot boxing is surprisingly good (Sugar Ray Leonard was a consultant). It’s the humans that are unpleasant.

In Time (2011)

Niccol imagines a dystopian near future in which Benjamin Franklin’s adage that “Time is money” is taken to a literal extreme. Human beings are genetically engineered to stop aging at 25, but they also come equipped with a literal biological clock, complete with digital readout on their forearms, that activates at 25 and begins counting down to zero.

Cowboys & Aliens (2011)

Putting Daniel Craig and Harrison Ford in Stetsons is clearly an excellent idea. Both men have faces made for Westerns, rugged and rough-hewn. There is a sense of stoic reserve and working-class grit about them; neither is the sort of man one can only imagine being an actor, or leading a life of privilege.

Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011)

Rise of the Planet of the Apes is a smartly made, effective movie — but what sort of movie is it, exactly?

Super 8 [video] (2011)

J. J. Abrams is a skilled storyteller, but has a bad habit of over-promising and under-delivering.

Green Lantern [video] (2011)

Green Lantern: my “Reel Faith” review.

Green Lantern (2011)

If only the filmmakers had put as much creative energy into the character of Hal Jordan as they did into his lovingly rendered CGI-enhanced suit, which pulses and glows as it hugs every bulge and swell on Ryan Reynolds’ impeccably sculpted torso.

Super 8 (2011)

Gone are the days when a movie like E.T. could open to a mere $11 million, build on word of mouth, and go on to earn more than $350 million in North America. Obviously, Abrams remembers those days. In a way, Super 8 is as derivative and familiar as anything in theaters today, only the movies it’s copying are all over a quarter of a century old: Spielbergian fare like The Goonies, E.T., Gremlins and Close Encounters, with echoes of earlier and later films.

Source Code (2011)

One could almost regard Moon as a warm-up for Source Code. Both films center on a solitary grunt who’s a cog in a much larger machine — an isolated man squirreled away in a cold, metallic space, unable to contact his loved ones, unsure exactly what’s going on, caught up in the seemingly impossible circumstances of a mission he doesn’t entirely understand. Both films raise questions of identity, memory, and human dignity in dehumanizing systems.

Tron: Legacy (2010)

In the years since Tron, of course, video games have come closer and closer to approximating reality, and computer-graphics in movies have gone further still — and, in a way, this is the problem with Tron: Legacy.

Inception (2010)

Inception is the most audacious and multifaceted Hollywood entertainment for grown-ups I’ve seen in years: a brainy, bravura achievement inviting comparison to the most inspired work of Hollywood visionaries from Michael Mann and Charlie Kaufman to Ridley Scott and the Wachowskis.

Avatar (2009)

James Cameron’s Avatar is a virtual apotheosis of Hollywood mythopoeia. It is the whole worldview and memory of contemporary Hollywood, given shape in a narrative and pictoral form that is stunning in its finality and grandeur. It is like everything and there is nothing like it.

9 (2009)

I don’t want to be too hard on 9. It’s the first film of a director who shows some promise, and a bravely idiosyncratic vision free from commercial pandering. It will probably fade quickly at the box office while soulless marketing machines like G. I. Joe and Transformers slog on and on. But Acker does himself no favors with rote anti-dogmatism and vapid characterizations.

District 9 (2009)

C. S. Lewis’s bleak prediction about human mistreatment of extraterrestrial creatures was framed in terms of human spacefarers encountering alien life on distant worlds, but the gist of his thesis is eminently applicable to the scenario proposed in District 9, a caustic and gory but sharply made sci-fi fable with a pungent South African flavor.

Moon (2009)

There’s an ambitious modesty to Duncan Jones’s debut film Moon, a smart, existential science-fiction drama with one onscreen actor that runs 97 minutes and goes nowhere more exotic than our planet’s natural satellite.

Star Trek (2009)

And so, for the first time in forever, we have Star Trek really and truly boldly going where we haven’t been before — taking Kirk, Spock, Bones, Uhura, Scotty, Sulu and Checkov on a brand-new adventure for the very first time. Before you know it, you’re getting to know old friends in an entirely new light. It’s like what Alan Moore said about Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns: “Everything is exactly the same, except for the fact that it’s all completely different.”

Battle for Terra (2009)

Watching Battle for Terra, the latest computer-animated offering presented in 3D, is little like stepping into a breathtaking cathedral in a strange city and finding a church play going on in the middle of it. The drama may be competently done, but it’s the least interesting thing in the room. You keep looking past the action, stealing glances to one side or the other, absorbed in the splendor of the setting. Earnest as the players are, the moralizing story draws you in only fitfully, and most of the time you’d rather steal away and just wander aimlessly from one corner to another, taking it all in.

Monsters vs. Aliens (2009)

As a tale of female empowerment and male comeuppance, Monsters vs. Aliens might have been provocative, like, 50 years ago. Today, nothing seems more subversive — and unlikely — than a family film with a heroic leading man who’s the equal of the leading lady — one boys can look up to without having to learn a lesson about male weakness. Now that’s a movie I’d like to see.

Return From Witch Mountain (1978)

Better structured and faster-moving than its predecessor, the sequel has more energy and wit in one sequence — the gold theft at the museum, in which a rolling stagecoach and floating manniquins evoke scenes from a Western — than all the special effects in the first movie combined.

Escape to Witch Mountain (1975)

One of the most popular Disney films of its era, Escape to Witch Mountain only loosely follows Alexander Key’s comparatively dark original tale about a pair of troubled orphans escaping a grim juvenile-hall orphanage and a sinister pursuer with the help of a heroic Catholic priest.

Race to Witch Mountain (2009)

Rather than a coming of age story, then, Race to Witch Mountain is a dark family action-adventure movie, with moderate doses of X-Files paranoia and Galaxy Quest sci-fi fandom satire, and a sometimes obnoxious rock soundtrack. It’s slicker, darker and funnier than the original films, though wall-to-wall action makes it a bit of a one-trick pony, and prevents the characters from catching their breath and displaying more than one side.

The Day the Earth Stood Still (2008)

I don’t object in principle to Keanu–Klaatu’s message. It’s just not a very interesting or enlightening thing for an ambassador from the universe to say. It’s sort of a letdown, not unlike like having the pope show up at your house only to check the batteries in your smoke detectors. There’s nothing wrong with that. You just hope he has more on his mind.

The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951)

More thoughtful and restrained than most sci-fi of the period, The Day the Earth Stood Still has aged better than almost all of its peers. … Decades later, it remains a thought-provoking, worthwhile parable.

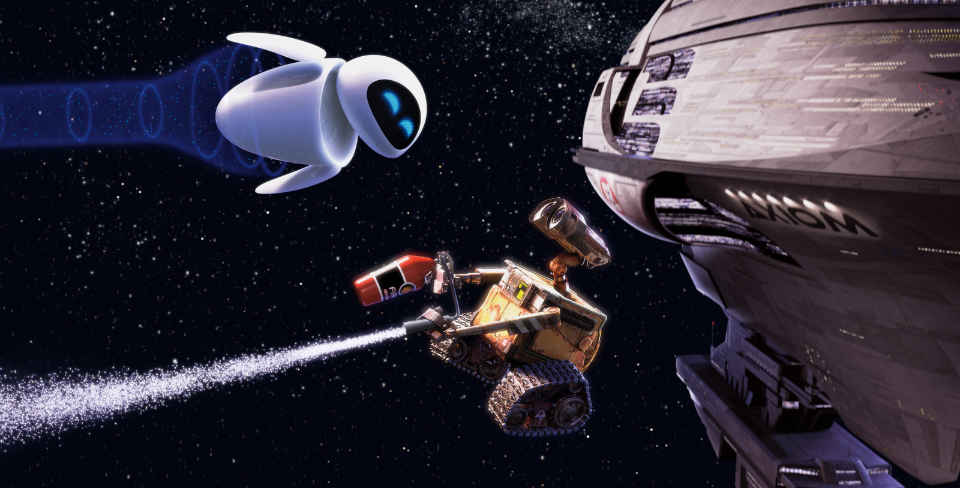

WALL•E (2008)

Even Pixar has never attempted anything on a canvas of this scale. From Monsters, Inc.’s corporate culture to Finding Nemo’s submarine suburbia, previous Pixar films have never strayed too far from the rhythms of real life. … WALL‑E creates a world that, despite clear connections to contemporary culture, looks and feels nothing like life as we know it, with unprecedented dramatic and philosophical scope.

Sunshine (2007)

For an hour or so it threatens to be one of the best movies of the year, but in the end, despite sci‑fi razzle-dazzle and some undeniably powerful images, Sunshine ultimately settles for puzzling rather than mysterious.

Déjà Vu (2006)

If it isn’t the brilliant film it could have been, Déjà Vu still contains enough flashes of that film to make it entertaining while you’re watching it. On reflection, though, it feels a bit like a shell game in which the conjurer himself has lost track of where the pea is supposed to be.

Zathura (2005)

Light on plot and story logic but strong on narrative thrust and fantastic imagery, it’s the most effective of the three films… Alas, Zathura is also a family film of the contemporary family as well as for it.

Serenity (2005)

For long-suffering “Firefly” fans, Serenity is at last a precious opportunity to find out what happens next, not to mention to learn the answers to nagging questions left hanging by the series’ abrupt demise — a journey that is at once thrilling, rewarding, heartbreaking, and wistful. For non-fans, Serenity is a delirious excursion into a world whose setting, characters and relationships are richer and more elaborate than any one-shot movie is likely to be.

Forbidden Planet (1956)

At once intelligent and campy, Forbidden Planet is an intriguing, perhaps overrated sci-fi classic that borrows plot points from Shakespeare’s The Tempest and strongly anticipates “Star Trek” in its sci-fi milieu — but its driving fears are the “monsters from the id,” the wayward, concupiscent passions of our own hearts.

Back to the Future (1985)

Brilliantly constructed and virtually universal in its appeal, Robert Zemeckis’s Back to the Future blends equal parts hilarity, nostalgia, science fiction, screwball comedy, and white-knuckle suspense in a complex storyline wound tighter than a yo-yo in a centrifuge.

Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (1984)

The Search for Spock may be the unappreciated middle child of the Trek franchise, but it’s still one of better and more indispensable episodes.

Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (1991)

The original Trek crew’s real last hurrah, Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country is a rousing sendoff for Kirk, Spock, and Bones, and a fitting transition from the original series’ Cold-War milieu to the Next-Generation age of engagement.

Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986)

With its time-traveling setting in the familiar milieu of the mid-1980s and its crowd-pleasing celebration of whales and conservationism, Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home is the most successful and widely appealing of the Star Trek films, and also the most idiosyncratic.

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982)

One of the strongest and most popular entries in the Star Trek film franchise, The Wrath of Khan has everything you could ask for in a good sci‑fi action-adventure film: sympathetic, well-drawn heroes, a terrific villain (Ricardo Montalban as Khan), exciting outer-space showdowns, sci‑fi wow factor (the Genesis effect), and a touch of reflective depth (the Enterprise crew finally faces up to age and mortality, and questions about the wisdom and consequences of playing God are hinted at).

Star Trek: Nemesis (2002)

(Written by Jimmy Akin) The main cast is no longer trapped in amber — never changing their relationships, never getting promoted, never leaving the Enterprise. They’ve become unstuck. It’s a sign of things to come.

The Island (2005)

The Island is the closest thing so far to a good Michael Bay film. Damning with faint praise, yes — but bear in mind that most of Bay’s filmography to date (Armageddon, Pearl Harbor, Bad Boys and Bad Boys II) deserves to be damned with loud damns. So let me repeat: The Island is Bay’s best film to date, and Bay’s best effort to date at a meaningful, thoughtful film.

War of the Worlds (2005)

Individual set pieces are riveting, and one seldom doubts that if alien tripods were actually wreaking havoc on the Earth, this is indeed very much what it would be like. Afterwards, though, one is left with little more than ashes.

An American mythology: Why Star Wars still matters

Star Wars is pop mythology — a "McMyth," as a recent critical article put it — but in our McCulture even a McMyth can be vastly preferable to no myth at all, and certainly to other, less wholesome mythologies (e.g., the Matrix trilogy). Even for those who generally prefer more traditional fare, there is still much to enjoy and appreciate in these half-baked, stunningly mounted fantasies of good and evil in a galaxy far, far away.

Star Wars: Episode II - Attack of the Clones (2002)

It doesn’t help that this is now the second Star Wars movie in a row in which the "wars" alluded to in the series title are still basically in the future (one climactic skirmish aside). Lucas should never have gotten bogged down in political debate, let alone given two whole films of it.

Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace (1999)

It’s not just that the banter and camaraderie of Luke and Han and Leia was so much more fun than the often wearying interactions of Anakin and Amidala and young Obi-Wan — though that’s part of it. More importantly, the stories themselves largely lack the strong center of good versus evil that was the heart of the original trilogy.

Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith (2005)

Crippled as he is by the decisions of the first two films, Lucas still manages to invest the final chapter of his sprawling space opera with the grandly operatic spirit of the original trilogy. It’s still cornball, yes, and with all the usual weaknesses. But Episode III at last has heart.

Star Wars [Episode IV – A New Hope] (1977)

An orphaned hero. An imprisoned princess. A wise old hermit. A magic sword. A fearsome dark lord. Such conventions are the stuff of myth and romance — yet, inexplicably, the first Hollywood film to give these mythic archetypes their due was not some Arthurian romance or epic costume drama.

Star Wars: Episode VI – Return of the Jedi (1983)

Thematically, where the first Star Wars movie offered a simple vision of good triumphing over evil, and The Empire Strikes Back expressed the problem of evil and the necessity of sacrifice, Return of the Jedi tackles nothing less than resisting temptation, compassion for enemies, and the possibility of redemption for even the most evil.

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (2005)

[T]he new Hitchhiker’s Guide has the whimsical look and absurdist feel of Adams’s universe, which remains best known in its novelized form but which originated as a radio series and was later realized as a BBC television series, a set of records, a computer game, and even stage adaptations. What it’s missing is the subversive commentary, the razor-edged deconstruction of human foibles. We get Adams the absurdist, but not Adams the provocateur.

Robots (2005)

Robots combines the visionary alternate world-building of Monsters, Inc., the flair for gadgetry and gimmickry of an old Fleishers cartoon, and most sneakily of all, the toybox nostalgia of the Toy Story movies, with cleverly worked-in toy and game references — “Operation,” Slinky, Wheelo — that will have adults grinning with recognition.

The Forgotten (2004)

Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (2004)

There are also plenty of film geeks who know and love the pulp fantasies of the early twentieth century, from Metropolis to the serialized swashbucklers of Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon. Some of these geeks are even creative enough to weave their own fantasies in the spirit of those classic films, even to the point of writing and directing the films themelves, though to date the only film actually made this way, as far as I know, is Star Wars. (Raiders of the Lost Ark, perhaps the ultimate serial-adventure homage, was conceived by George Lucas but written by Lawrence Kasdan and directed by Steven Spielberg.)

Planet of the Apes (1968)

Adapted by Rod Serling from Pierre Boulle’s Swiftian social satire, Planet of the Apes is basically a feature-length "Twilight Zone" episode, with all that that implies for good and ill. There’s an ironic sci-fi reversal of real-world conditions, a rather thin plot padded to fill out the running time, heavy-handed but sincere allegorical moralizing, thought-provoking social satire, and a stunningly imagined climactic twist.

Metropolis (1927)

Surreal, sprawling, and operatic, drawing on biblical and medieval Christian imagery as well as H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine, Fritz Lang’s deeply influential pulp allegory Metropolis colonized a new realm of the imagination that has shaped subsequent science fiction from Flash Gordon to Star Wars, from "The Jetsons" to Blade Runner.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

2001: A Space Odyssey doesn’t just depict a quantum leap forward in human consciousness — it practically requires such a leap, on an individual scale, from the viewer. Like the hominid in the first act who looks at a bone and suddenly sees what no hominid has ever seen before, one must watch 2001 in a different way from other films.

Sculpting in Bullet Time: The Matrix Trilogy Revisited

The Matrix is simultaneously a philosophical model and a popular myth — a postmodern analogue to both Plato’s cave and Homer’s Odyssey, Descartes’ daemon and Pilgrim’s Progress, the brains-in-vats scenario and Star Wars.

The Matrix Reloaded (2003)

Morpheus’s expository speech to Neo in the first film about the history of the power behind the Matrix — particularly the bit about the solar issue and the moment when he holds up the battery — is both the least persuasive and the least interesting thing about the film. It’s a perfunctory plot-level explanation that one accepts for the sake of the action and the hero’s journey, not something one particularly cares about for its own sake.

The Matrix Revolutions (2003)

Beyond that, unlike Reloaded, which featured an impressive but hardly groundbreaking freeway chase scene as its biggest set piece, Revolutions has startling new sights to offer, notably a spectacular siege scene that recalls the first act of The Empire Strikes Back with its Walker attack on the Hoth Rebel base. In fact, The Matrix Revolutions arguably had the potential to be the Empire Strikes Back to The Matrix’s Star Wars, had the Wachowskis not squandered that opportunity six months ago with Reloaded.

The Matrix (1999)

Be that as it may, scratch the surface of the vast body of commentary and discussion devoted to The Matrix, and you could start to get the impression that Morpheus’s comment is a fairly accurate description of the film itself. The Matrix has been described as everything from a neo-gnostic parable to a Christian allegory, from a strikingly innovative action film to a derivative rip-off of kung-fu clichés and stock anime conventions. Commentators have found influences from Plato and Descartes, Lewis Carroll and Star Wars. At the end of the day, can anyone really say what The Matrix is?

Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines (2003)

Yet against all odds, T3 is a smart, rousing extension of Cameron’s paranoid fantasy that not only meshes seamlessly with the past and future continuities of the earlier films, but actually advances and develops the series’ apocalyptic mythology.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004)

Obviously, a Kaufman film called Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind isn’t going to be as cheerful and wholesome as the title might suggest. Despair, isolation, and loneliness continue to hang like a fog across his world. Eternal Sunshine also resembles his other films in its characters’ milieu of general dissipation, casual sex, drug use, and so on.

Vanilla Sky (2001)

Like puzzle movies from Memento to Fight Club, Vanilla Sky is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. The problem is, the mystery and the enigma are in one movie, and the riddle’s in an entirely different movie — in fact, in an entirely different genre of movies.

Men in Black (1997)

Based on the whimsical comic book series of the same name, Men in Black looks superficially like another Independence Day-style big-budget summer special-effects extravaganza with a catchy three-letter acronym. Yet MIB is smarter, leaner, funnier, and more human than most entries in the genre, relying less on spectacle than on the chemistry of the two leads and the wit of the script for its appeal.

Signs (2002)

Signs has the

heart that was lacking in Unbreakable, but stumbles badly

in its treatment of the paranormal, in this case the world of

"X-Files" / "Twilight Zone"

Fantastic Voyage (1966)

A landmark of 1960s sci-fi, Fantastic Voyage remains compelling entertainment despite dated special effects, deliberate pacing, and indifferent dialogue and acting, thanks in part to the genuine wonder it brings to its premise.

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982)

(Review by Jimmy Akin) Khan stood above the crowd of crass, original series Klingon captains, Star Fleet officers gone bad, and assorted alien malefactors. He was something different. Strong. Mysterious. Charismatic.

Planet of the Apes (2001)

Helena Bonham Carter is also convincingly simian as the chimpanzee Ari, though less so than Thade, since she has to be visibly feminine and potentially attractive to the human lead (Mark Wahlberg). But the gorillas, like Attar (Michael Clarke Duncan) and Krull (Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa), are as compellingly realistic as Thade, if not quite as expressive.

Solaris (2002)

This year’s Solaris from writer-director Steven Soderbergh (Erin Brockovich is part of an ongoing trend toward science fiction aspiring to the tradition of 2001. Not long ago, science fiction had become a wasteland of forgettable, mindless action flicks. The year 2000, for example, gave us Red Planet, Battlefield Earth, The 6th Day, Hollow Man, Pitch Black, and Supernova (as well as Mission to Mars, which didn’t fit the mindless-action pattern but managed to be lame anyway). Even the previous year’s The Matrix was notable primarily for its kinetic impact and craft; the story, though clever, was long on allusions and short on genuine resonance.

K-PAX (2001)

Prot pulls off these party tricks quite convincingly. Yet get him started on his theories about mankind, family, society, and the like, and the spell is broken: He’s clearly delusional. Not that I’m saying anything about the truth or falsehood of his claims. Prot may very well be an alien. That doesn’t mean he isn’t delusional.

Simone: Reality and Fantasy in Hollywood (2002)

The first line of the film’s closing credits read, "Introducing S1m0ne as Herself." At the time of the early-look screening I attended, no further information about "Simone" was readily available. The movie’s production notes, website, and Internet Movie Database entry were all silent about who, or what, Simone might be.

Men in Black II (2002)

Beyond more action and bigger effects, the sequel brings nothing new to the table. You’ll wait in vain for satirical "revelations" about the presence of aliens among us to match the wit of the jokes in the original about cab drivers or the World’s Fair. Instead, we get limp gags like the one about the Post Office being staffed by aliens. (Why? Is it a joke about postal efficiency? The "going postal" stereotype? The fact that they make rounds? What?)

Lilo & Stitch (2002)

Lilo & Stitch is a unique imaginative achievement that succeeds in its own right, without laying down any kind of template for future films to follow. Attempts to repeat its success, to make it into a formula, would be a dismal failure, unless perhaps the formula were to be "Give the creative people room to try something new and let them work without a safety net." What a concept.

Minority Report (2002)

Spielberg has always known how to manipulate an audience’s emotions, a knack he makes effective use of here. Humor alternates with squirming discomfort and emotional release as the director pokes fun of Cruise’s sex-symbol status in a couple of funny incidents, then leaves us wincing with a number of scenes involving eyeballs, or a character fumbling blindly for the one edible sandwich in a squalid refrigerator.

Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

The Empire Strikes Back is the backbone of the Star Wars saga. It takes the story and themes of the first film into deeper waters.

Star Wars [Episode IV – A New Hope] (1977)

(Review by Jimmy Akin) Like earlier pulp films, Star Wars draws on mythic and fairy-tale archetypes: a young orphan-hero; a mysterious wizard-mentor; a fearsome dark lord; a magical sword; a princess held prisoner; a gallant rescue mission. Yet on a deeper level, Star Wars is more convincing as a myth or fairy tale in its own right.

Galaxy Quest (1999)

Besides satirizing Star Trek’s fan base, Galaxy Quest also takes aim both at the absurdities of the show itself and also at the behind-the-scenes reality. Most of the obvious Trek conventions are targeted: the principle that any extraneous character on an away mission always dies; the shipwide crisis that requires crew members to crawl through endless ducts; the isolation of the captain on a hostile planet where he must do hand-to-hand combat with an alien monster.

The Time Machine (2002)

The Time Machine is so sloppy that it makes Kate and Leopold look like Back to the Future. It’s also pitiful entertainment, succeeding neither as spectacle, as action-adventure, or as love story.

Red Planet (2000)

At least there’s stuff worth looking at. First-time film director Antony Hoffman has an eye for visuals; and the Martian landscape, shot in an Australian quarry and a Jordanian wadi, is stark and compelling. Then there’s the constantly swiveling, gyrating AMEE, a preposterous plot device of a robot which, in its (or "her") feline grace and unlimited range of free-flowing motion, resembles a high-tech computer-generated cross between Transformers and Battle Cats. I liked the little touches almost as much: the crew uses nifty, collapsible hand-held computers with a flexible, glossy display that pulls out from and rolls up into a cylindrical CPU like a window shade, looking for all the world like something you might actually see in a Macintosh commercial from 2050, when the movie is set.

Kate and Leopold (2001)

Whenever Kate and Leopold is about Kate and Leopold (Meg Ryan and Hugh Jackman, respectively), it just about works.

Frequency (2000)

This is a film about the legacy of fatherhood and the inheritance of sonship, about the unbreakable connection and the unbridgeable gap between one generation and the next. It is a celebration of masculinity, but it contemplates how men relate to women as an index of their manhood.

Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within (2001)

Based on a computer game, Final Fantasy is always interesting to look at, and is sometimes visually spectacular, but it hasn’t transcended its gaming origins. The sci-fi scavanger-hunt premise hasn’t been fleshed out into a coherent or satisfying story. The heroes, though eye-poppingly rendered, remain emotionally as one-dimensional as any computer-game avatar. Even basic rules and motivations never become clear.

E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

“The story of a boy and his dog,” writes one critic. “Close Encounters for kids,” writes another. Still others focus on the Christological resonances, particularly in connection with another messianic sci‑fi film, The Day the Earth Stood Still, with its peaceful visitor from the heavens who dies and rises again.

Battlefield Earth (2000)

Here is the closest thing to a positive statement I can make about Battlefield Earth: Although it is an adaptation of a novel by L. Ron Hubbard, the founder of the sect of Scientology - and although it stars John Travolta, one of Hollywood’s most high-profile Scientologists and a long-time champion of this project - Battlefield Earth is not a cryptic tract or allegory of Scientology.

Armageddon (1998)

“Talk about the wrong stuff” is one officer’s disparaging comment as Willis’ team struts about NASA ostensibly preparing for their mission, hamming it up like class clowns in high school, ridiculing the process, flaunting their lack of couth like a badge of honor — all but letting their butt cracks stick out. Yes, in this film the honors science students are obliged to sit back and watch as the shop class saves the world.

A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)

A.I. is a science-fiction fairy tale: a terrible, revisionistic revisiting of "Pinocchio," the story of the little manmade boy who wants to be real — as told by a nihilist who condemns Gepetto for creating Pinocchio, the world for laughing at him, and the Blue Fairy for leading him on when he’s better off being made of wood, which will after all be around long after Gepetto is pushing up daisies.

The 6th Day (2000)

Arnold Schwarzeneggar’s latest vehicle brings us to a rather well-realized, not-too-distant future ("sooner than you think" according to an ominous caption) in which human cloning is possible but forbidden by "sixth-day laws" (so called after the sixth day of creation week in Genesis 1, the day when God created man).

Planet of the Apes (1968)

(Review by Jimmy Akin) Based on a book by French novelist Pierre Boulle, Planet of the Apes is essentially a big-screen version of a Twilight Zone episode (not surprising since Twilight Zone-creator Rod Serling was a co-author of the screenplay).

Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

(Review by Jimmy Akin) In the process of adding new depth to familiar subjects, the film often takes unexpected turns. One of the subtlest of these — so subtle that it tends not to be noticed by the audience — involves the mythic dimensions of Luke’s transformation from backwater farmboy to mystical adept.

Star Wars: Episode VI – Return of the Jedi (1983)

(Review by Jimmy Akin) In the end, Star Wars reveals itself to be not just the most ambitious science-fiction epic brought to the big screen but a story expressing the importance of family and love, the danger of moral corruption, and the possibility moral redemption.

Recent

- Benoit Blanc goes to church: Mysteries and faith in Wake Up Dead Man

- Are there too many Jesus movies?

- Antidote to the digital revolution: Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality

- “Not I, But God”: Interview with Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality director Tim Moriarty

- Gunn’s Superman is silly and sincere, and that’s good. It could be smarter.

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.