Search Results

110 records found

The Tree of Life: God and Man Cross-examined

Here is a film that not only asks, with unusual insistence, why God allows suffering, but contemplates God’s own answer to that question in the Book of Job, amplified by the sweeping vistas of the natural world available to modern science, the Hubble telescope and Hollywood special effects: God did all this; who are we to think we can judge or question him? It also asks why a stern, bullying father hurts his children. Is God like that father?

The Tree of the Wooden Clogs (1978)

Critic Dave Kehr of the Chicago Reader calls The Tree of the Wooden Clogs "less an advance over the standard film festival peasant epic than an unusually accomplished rendition of it," and speaks of a "Marxist sentimentalism" inherent in its subject matter and approach. This seems to me misleading. Olmi’s film may be best thought of, not as an attempted advance over the typically Marxist neorealist peasant epic, but as a redemption of it.

A Triduum ritual: The Miracle Maker

Our seasonal movie-watching during Advent, Lent, and the Christmas and Easter seasons varies from year to year, but Triduum is always the same.

Triple Threat: Fox’s Spring 2005 Family Film Lineup

Typically, the spring movie season has at most one decent film for family audiences. Last year it was Two Brothers; offerings from previous years included Holes (2003), Ice Age (2002), Spy Kids (2001), and The Emperor’s New Groove (2000).

Tron: Legacy (2010)

In the years since Tron, of course, video games have come closer and closer to approximating reality, and computer-graphics in movies have gone further still — and, in a way, this is the problem with Tron: Legacy.

The trouble with angels: Heavenly messengers according to Hollywood

The popular eschatological confusion that we “become angels” when we die may be a headache for catechists, but only a curmudgeon would object to a Hollywood fable taking this sort of creative license. Still, there’s no reason for all movie angels to be as angelically incorrect as Clarence.

The trouble with Christmas movies

“What are your favorite Christmas movies?” As a Catholic film critic, I get this question several times every December, often on the air or via social media. The question, alas, touches on a sore subject for me.

The Trouble With Trailers

Have movie previews gotten to be too much? Parents have been complaining for years about inappropriate coming attractions playing before movies aimed at younger or more innocent viewers—and it’s getting worse.

Troy (2004)

So long is the shadow of The Iliad over the history of Western literature that before considering the merits of Wolfgang Petersen’s Troy it may be helpful to recall that the story of the Trojan War was not only likely told by poets long before Homer, certainly after Homer it has been retold and reworked by numerous poets and writers, including Virgil, Euripides, Quintus, Chaucer, and Shakespeare.

True Grit (2010)

The Coens’ film is franker than its predecessor about the violence of the old West and of Portis’s book; it is also franker about the religiosity, from frequent scriptural references to a score shot through with hymnody.

The Truman Show (1998)

Peter Weir’s The Truman Show is a remarkably layered achievement: a deceptively simple fairy tale; a hilariously subversive satire of media excess and the erosion of privacy; a sly exploration of the paranoid, solipsistic fear that the world around one is somehow staged for one’s benefit and everyone else is in on it; and finally an elegant parable about truth and happiness with evocative religious resonances.

The truth behind one of Netflix’s most popular shows

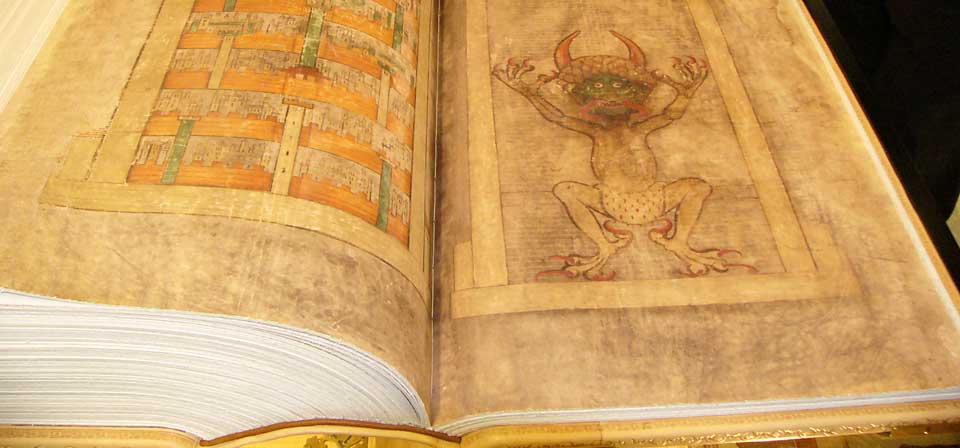

Want to know the truth behind the “Devil’s Bible”? Or the Dead Sea Scrolls? How about one of the Old Testament’s two famous arks? Curious about UFOs, Bigfoot or the Bermuda Triangle?

Trying to reach the sublime: Robert Eggers, cinematic poet of the past

In the Viking epic The Northman, the arthouse horror auteur behind The Witch and The Lighthouse takes on his most ambitious challenge to date.

Tsotsi (2005)

Tsotsi seems almost entirely severed from human values, and his seemingly total moral apathy rattles the conscience-stricken Boston. “Decency, Tsosti,” Boston harangues. “Do you know the word?”

Tuck Everlasting (2002)

The story, originally set in 1880 but moved to 1914 for the movie, concerns a sheltered young girl from a well-to-do family who is called "Winifred" by her overprotective parents and grandmother, and might be called "Winnie" by her friends if she had any. Winnie (Alexis Bledel of TV’s "Gilmore Girls") is so timid that when she decides to run away from home, she heads for the family-owned woods adjacent to her house, never actually setting foot off her parents’ property.

![Tully [video]](/uploads/articles/tully-vid.jpg)

Tully [video] (2018)

A messy, thought-provoking film about motherhood from the makers of Juno and Young Adult? Go figure.

Turbo (2013)

At some point, alas, it becomes apparent that Turbo’s more daring elements are all surface, and the story is locked into a well-worn path to an all-too-obvious destination. Writing about Monsters University, I noted that, like many other Pixar films, it pours cold water on the familiar family-film platitude that you can achieve anything you put your mind to if you just want it enough. Turbo embraces the platitude.

The Tuxedo (2002)

The suit is in fact the Tactical Uniform Experiment (TUX), a high-tech weapons system that acts directly on the user’s nervous system, instantly enabling Jimmy — who, unlike most of Jackie’s characters, has no special skills of his own — to dance like Fred Astaire, climb walls and ceilings like Spider-Man, and, of course, fight like Jackie Chan.

Twentieth Century (1934)

Often credited as the first screwball comedy, Howard Hawks’s Twentieth Century is an acerbic satire of show-business ego and superficiality starring John Barrymore and Carole Lombard.

Twilight – Breaking Dawn: Part 1 [video]

Here’s my 30-second take on Twilight – Breaking Dawn: Part 1.

Recent

- Crisis of meaning, part 3: What lies beyond the Spider-Verse?

- Crisis of meaning, part 2: The lie at the end of the MCU multiverse

- Crisis of Meaning on Infinite Earths, part 1: The multiverse and superhero movies

- Two things I wish George Miller had done differently in Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga

- Furiosa tells the story of a world (almost) without hope

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.