Search Results

41 records found

Joseph of Nazareth: The Man Closest to Christ

I don’t often discover a new angle on a biblical text from a Bible movie, but Joseph of Nazareth suggests an attractive approach I had never before considered to a deceptively knotty passage in St. Matthew’s Gospel, namely, the passage in Matthew 1 in which Mary has been found to be with child by the Holy Spirit, and Joseph resolves to “divorce her quietly.”

Joseph: King of Dreams (2000)

Joseph’s own dreams — the two biblical ones plus an extra one — are the best; I caught my breath at the first glimpse of these dreams, which look like living, flowing Van Goghs. The dream-sky swirls like Starry Night, and the grass ripples under the dream-Joseph’s feet like ripples in a pond. The dreamlike quality of these sequences is undeniable and memorable.

Joy to the World: A Christmas Carol and the attack on — and defense of — Christmas

Scrooge’s conversion, like many conversions, is just such a dramatic revelation out of crisis, "as sudden as the conversion of a man at a Salvation Army meeting," says Chesterton, adding slyly, "It is true that the man at the Salvation Army meeting would probably be converted from the punch bowl; whereas Scrooge was converted to it. That only means that Scrooge and Dickens represented a higher and more historic Christianity" ("Christmas Books").

Judas: Jesus in the Eyes of His Betrayer

Judgment at Nuremberg (1961)

Downbeat, intelligent, and compelling, the film is brilliantly constructed and acted, bringing lucid, forceful moral argumentation as well as emotional sympathy to both sides without tipping its hand until the powerful climax. Tribunal justice Dan Hayward (Spencer Tracy) is the ideal foil for the film’s rhetoric: a self-deprecating, folksy American circuit court judge with no ax to grind and a winsome appreciation for his own obscurity, knowing he’s sitting in judgment of defendants no one else wanted to judge.

Judgment Day for Camping

I don’t like to see anyone’s views, right or wrong, misrepresented or distorted. In my Evangelical Protestant days, I often found myself inadvertently explaining Catholic beliefs against Protestant distortions of those beliefs, not because I accepted them as true, but simply because I felt we should be clear on what other people do and don’t think.

Julie & Julia (2009)

Toward the end, the two storylines almost converge as Julie’s blog comes to Julia’s attention — and Julia’s reported response leaves Powell in tears. How that twist strikes you make depend in part on which storyline you have felt closer to, on whose movie it is for you. Either way, there’s something for everyone, and if there’s a couple of brief bedroom scenes, for once they involve happily married couples.

The Jungle Book (2016)

Like Kenneth Branagh’s Cinderella last year, The Jungle Book offers a lavish new reimagining of a beloved story, blending elements from the original literary source material with the classic animated Disney version.

The Jungle Book (1967)

As interpreted by Disney and director Wolfgang Reitherman, The Jungle Book is essentially a coming-of-age parable about carefree childhood and adult responsibility, embodied respectively by Mowgli’s two mentors, Baloo the bear and Bagheera the panther (Sebastian Cabot).

The Jungle Book 2 (2003)

The voices are different, but the story is the same.

Jungle Cruise (2021)

Dwayne Johnson and Emily Blunt are highly watchable, but Disney’s latest theme-park movie trails haplessly in the wake of Pirates of the Caribbean without a ghost of its inspiration.

Junior Knows Best

In theaters right now are two charming and visually engaging animated films at opposite ends of the budget spectrum, different in many respects but with some interesting overlap as well. One is How to Train Your Dragon, DreamWorks’ big-budget CGI adaptation of a popular children’s book. The other is The Secret of Kells, an Oscar-nominated Irish animated indie made on a comparative shoestring budget, now in limited release.

Junior Knows Best: We need to talk about cartoon parents

I don’t expect animated heroes to have uniformly ideal, harmonious family lives. It’s not realistic — and it doesn’t make for good drama, which needs conflict. The ubiquity of the pattern, though, is striking.

Juno (2007)

Yet it’s right around this point that Juno, which has been clever and insightful, unexpectedly reveals hidden layers of complexity and depth.

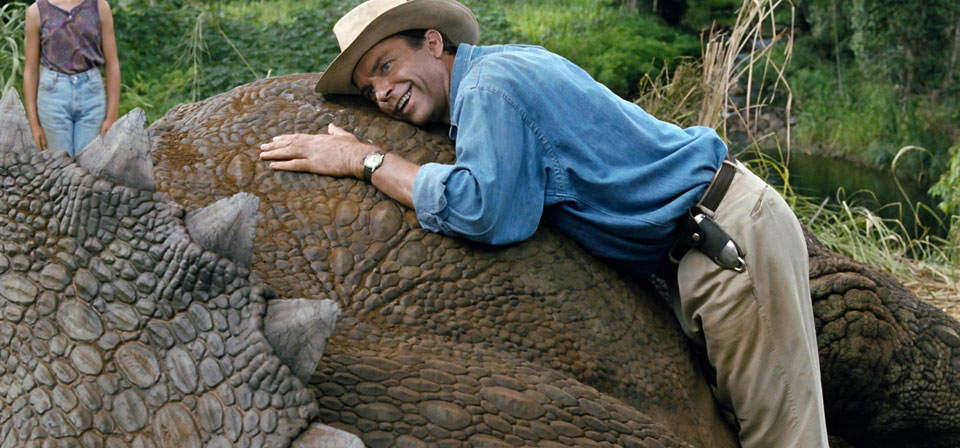

Jurassic Park (1993)

In the twenty-odd years since Jurassic Park pioneered the use of photorealistic computer-animated living creatures integrated into a live-action film, computer animation has become even more prevalent. Yet in all that time, it’s hard to think of a single blockbuster spectacle that uses computer imagery to achieve a similar sense of awe and grandeur.

Jurassic Park [video]

Jurassic Park in 60 seconds: my “Reel Faith” review.

Jurassic World (2015)

Pratt more than delivers. You could almost say he manages to stand in for Sam Neill, Jeff Goldblum and Laura Dern. He’s got Neill’s toughness, Goldblum’s humor and Dern’s down-to-earthness. His character, Owen Grady, is Jurassic World’s velociraptor trainer, and in a terrific early set piece Pratt persuades me that he’s capable of standing up to three raptors armed with nothing but charisma and nerve.

Jurassic World Dominion (2022)

The word “dominion” is uttered once in Jurassic World Dominion, in an oblique, irreverent allusion to Genesis 1. “Not only do we lack dominion over nature, we are subordinate to it,” asserts Dr. Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum) in one of his trademark, smugly iconoclastic epigrams. Later in the same speech, though, Malcolm turns with surprising optimism to the power of genetic science to shape the future. Does he really believe this? Is this speech coherent? Is the film itself coherent?

Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom (2018)

Apparently velociraptor is the cowbell of dino design and the filmmakers are Christopher Walken.

Just Like Heaven (2005)

Just Like Heaven is the first Hollywood film since Return to Me that I would put in the same league as that earlier film, and that’s saying something.

Recent

- Benoit Blanc goes to church: Mysteries and faith in Wake Up Dead Man

- Are there too many Jesus movies?

- Antidote to the digital revolution: Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality

- “Not I, But God”: Interview with Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality director Tim Moriarty

- Gunn’s Superman is silly and sincere, and that’s good. It could be smarter.

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.