Search Results

103 records found

Harry Potter vs. Gandalf

What defines morally acceptable use of good magic in fiction? Where, and how, do we draw the line? How do we distinguish the truly worthwhile (Tolkien and Lewis), the basically harmless (Glinda, Cinderella’s fairy godmother), and the problematic or objectionable (“Buffy,” The Craft)? And where on this continuum does Harry Potter really fall?

Harry Potter vs. the Pope?

To summarize: What we have is an informal, brief, obscurely worded opinion, in a private letter that may or may not have been written by Ratzinger himself, apparently declining to comment on a book that he may or may not have perused about a series of books he may or may not have ever laid eyes on.

Harry Potter’s Empire Strikes Back? Don’t Make Me Laugh

12 reasons why Deathly Hallows: Part 1 is no Empire Strikes Back … or even The Two Towers.

![The Hate U Give [video]](/uploads/articles/thehateugive.jpeg)

The Hate U Give [video] (2018)

If a parent having The Talk with their kids to you means the birds and the bees, you ought to watch this movie.

A haunting film about the “martyr of Auschwitz”

Nearly two decades before his Oscar-winning role as a Jew-hunting Nazi in Quentin Tarantino’s lurid WWII fantasy Inglourious Basterds, Christoph Waltz played an Auschwitz survivor whose escape is linked to the death of one of Auschwitz’s most celebrated victims, St. Maximilian Kolbe.

Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison (1957)

Like director John Huston’s similarly themed The African Queen, the film finds conflict mixed with romantic tension in a tale of a demure religious woman thrown together with a rugged male loner. Here, though, the complicating factor is not fastidiousness on the part of the religious woman, but the woman’s vocation.

Hellboy (2004)

The best thing about Hellboy is Hellboy. And he’s a demon.

Hellboy and Spiritual Warfare, Hollywood Style

You won’t find the gospel in movies like Hellboy. What you may find is signs of a world that has been touched by the gospel — a world that retains some awareness of sinister forces to be avoided or resisted, of evil that cannot be overcome by therapy or education or communication, that calls for a response from another realm entirely.

Hellboy II: The Golden Army (2008)

Bigger effects and badder creatures make Del Toro’s second take on Hellboy more entertaining than the original, but something’s still missing in the story of the super hero from hell.

The Help (2011)

Based on Kathryn Stockett’s best-selling 2009 novel, The Help is largely about the daily humiliations and injustices to which black maids and nannies working in white homes were subject, and the invisibility of these humiliations to their white employers, until, in this fictional account, their stories are told, first in secret and then in public.

Henry Poole is Here (2008)

Like M. Night Shyamalan’s Signs, Henry Poole simply divides the world into two groups of people: those who see signs and miracles, and those who see only coincidence. How either group arrives at or explains particular conclusions, not to mention how people decide which group they belong to in the first place, isn’t explored. We just get Henry with his arms folded defiantly across he chest intoning “Coincidence,” and everyone else serenely shrugging their shoulders saying “Faith.”

Hercules [video] (2014)

A question I couldn’t get to in 60 seconds: What’s the real story with the creepy, green spaced-out tribal warriors? Can anyone explain that?

Here I Stand: The Good and Bad in Eric Till’s Luther

In one sense, I’d like to see more films like this made. At the same time, Luther is also a seriously flawed film. Relentlessly hagiographical in its depiction of Luther and one-sidedly positive in its view of the Reformation, the film also distorts Catholic theology and significant matters of historical fact, consistently skewing its portrayal to put Luther in the best possible light while making his opponents seem as unreasonable as possible.

Hereafter (2010)

Hereafter is demeaning both to believers and to unbelievers, and for the same reason: It stacks the deck too heavily in one direction. “The evidence is irrefutable,” a researcher tells TV journalist Marie Lelay (Cécile de France), dropping a sheaf of documentation on life-after-death experiences in her lap. “The X-Files” told us that the truth was out there, but Mulder and Scully never had it this easy.

Hero (2002)

The story is pure Hong Kong melodrama, set at the dawn of the Chinese Imperial Era in the third century BC. … Yet there’s nothing even marginally conventional about Hero’s overpowering visual splendor, its effulgent riot of color and texture, its overwhelming spectacle of scale.

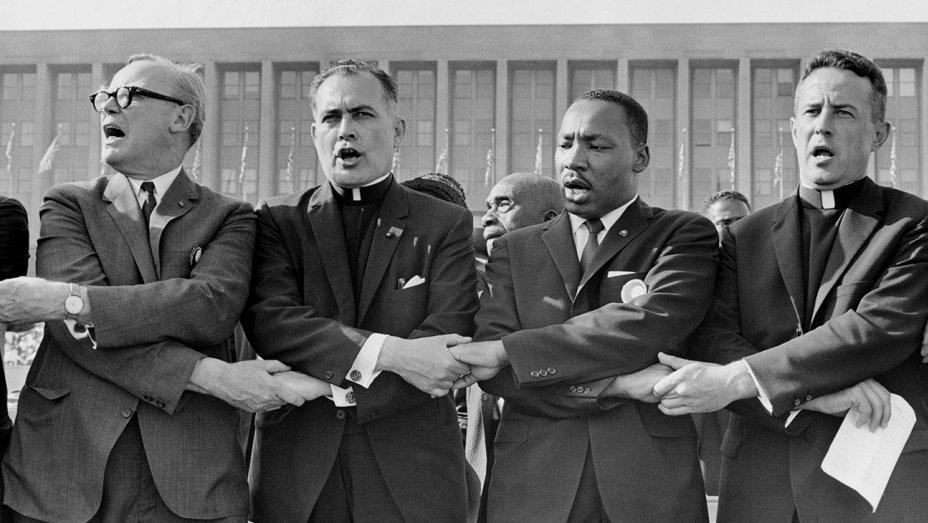

Hesburgh (2019)

Patrick Creadon (I.O.U.S.A.) offers a compellingly attractive if one-sided portrait of a figure of exceptional gifts, astonishingly diverse accomplishments and extraordinary influence.

Hey Arnold! The Movie (2002)

(Written by Jimmy Akin) Nickelodeon’s animated "Hey Arnold!" TV series, created by the Snee-Oosh animation house, is one of the better cartoon shows around.

Hey, DC / Arlington area!

Local to the Washington metropolitan area? This Friday, May 13th, I’ll be at the FORUM Arlington talking about cinema and Catholic faith — at least, if the title of my talk, “A Ray of God: Movies and Catholic Teaching” is any indication.

Hidalgo (2004)

Viggo Mortensen, back in the saddle in his first post-Aragorn role, is entertaining as the laconic, disarmingly soft-spoken cowboy hero called "Far Rider" by the American Indians in honor of his fleet-footed mustang Hidalgo. Remarkably, Disney doesn’t whitewash the more politically incorrect elements of Hopkins’ tale: The Arabs Hopkins meets are sophisticated and well-bred but also imperious, condescending to non-Muslim "infidels," slighting to their women, callous to slave trade, and in some cases duplicitous and murderous — though others are loyal and honorable, and there’s also an explicitly identified "Christian" (i.e., European) character who’s a villain.

Hidalgo (2004)

(Review by Jimmy Akin) Hidalgo is the story of a horse — and the cowboy who rides him.

Recent

- Benoit Blanc goes to church: Mysteries and faith in Wake Up Dead Man

- Are there too many Jesus movies?

- Antidote to the digital revolution: Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality

- “Not I, But God”: Interview with Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality director Tim Moriarty

- Gunn’s Superman is silly and sincere, and that’s good. It could be smarter.

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.