Search Results

81 records found

Final Updates: Italian pilgrimage blogging

I’ve been on vacation this week—hence the absence of other new material—but for those who’ve been following my Italian pilgrimage blogging at NCRegister.com, I’ve just posted the final two parts, Update 5 and Update 6.

Finding Dory (2016)

Hank the octopus is a particular standout. Hank’s squash-and-stretch movements push computer animation to yet another high-water mark, and his mad skills are highly entertaining — so entertaining, in fact, that I kind of wish the movie had been about him.

Finding Nemo (2003)

(New review for 3-D rerelease) Andrew Stanton’s Finding Nemo is the best father-son story in all of Hollywood animation, and maybe animation generally. It’s also a stunningly gorgeous film that exploits the potential of computer animation like no film before it and few films after it.

Finding Nemo [video]

It still makes me cry every time.

Finding Neverland (2004)

The film depicts Barrie coming into the Llewelyn Davies boys’ lives like Robin Williams into the lives of his students in Dead Poets Society. This isn’t a story about magical childhood soaring where no adult can follow, but about a magical adult imparting the gift of imagination to children.

Fires on the Plain (1959)

Unlike Ichikawa’s The Burmese Harp, which preserved the overt Buddhist milieu of the original book, the film version of Fires on the Plain eliminates the religious, in this case Christian, dimension of its source material. While both films may be called “anti-war” or “pacifist,” The Burmese Harp has a larger humanistic perspective on the riddle of suffering and the place of human values amid inhuman circumstances that goes far beyond a simple deploring of war. Fires on the Plain doesn’t transcend the “war is hell” genre in the same way, though the aesthetic rigor of its descent into hell is about as exacting and definitive as such a thing can be.

First Man (2018)

First Man is Damien Chazelle’s third film in a row about special individuals whose quest to achieve great things is linked to emotional isolation from others.

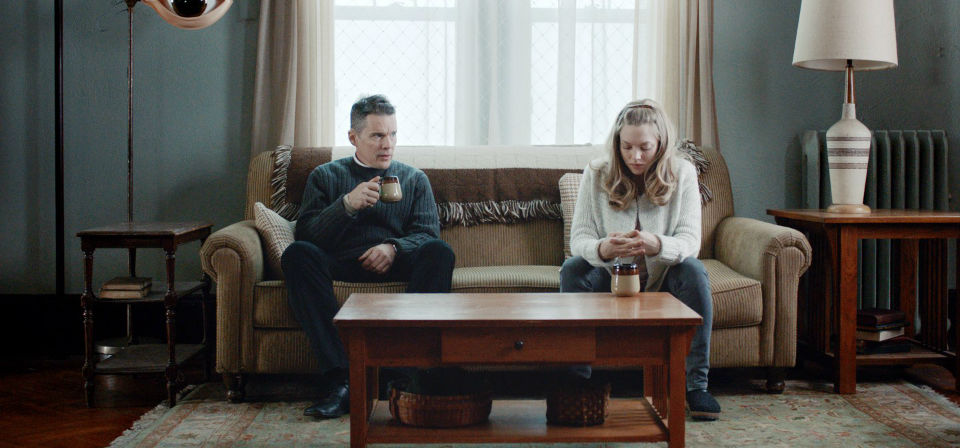

First Reformed (2018)

Schrader makes greater use than ever before of what he calls the “transcendental toolkit” — but it’s still very much a film from the writer of Taxi Driver. If Toller partly evokes Bresson’s wan, saintly curé, in time we see that he’s also part Travis Bickle, which can be as difficult to watch as it sounds.

Flags of Our Fathers (2006)

Even today, the iconic, Pulitzer-winning 1945 photograph of five US Marines and a Navy corpman raising the American flag on Iwo Jima retains an extraordinary power. Like a Norman Rockwell painting, Joe Rosenthal’s famous photograph tells a story, creates a mood, evokes an ethos, and elicits a metaphorical or allegorical response, all at the same time.

Flight of the Phoenix (2004)

This provocative comeuppance for can-do American spirit is thrown to the winds in the remake, which from the outset establishes pilot Frank Towns (Dennis Quaid) and his co-pilot A.J. (Tyrese Gibson in the Attenborough role) as bullying, swaggering creeps with no redeeming traits who exist in order to be taught a lesson. They’re gratuitously abusive to the ragtag team of abruptly unemployed oil-riggers they’ve come to evacuate. Their arrogant repartee in the opening minutes is so full of leering sexist humor (Frank’s the sort of guy who can’t even buckle his seat belt without making a lewd remark about it) that by the time A.J. observes of the massive sandstorm into which they’re flying, "That’s a big one, Frank," we can tell it must be serious, since Frank makes no crass response.

Flight [video]

Flight in 60 seconds: my “Reel Faith” review.

The Flintstones in Viva Rock Vegas

I think that a similar dynamic may be at work in The Flintstones in Viva Rock Vegas, a prequel to the 1994 film that purports to tell us how young Fred and Barney first met and married Wilma and Betty (respectively). Kids may happily gobble up Viva just because it’s a movie based on a popular cartoon show; and even parents desperate for watchable family entertainment may allow themselves to be seduced by its colorful set pieces and the goofy charm of the cast. But really, it’s not at all good. Not so much nasty, like coffee ice cream to a child; but rather bland, inert, and joyless, like some insipid sugar-free fat-free Frozen Dessert Product.

Flipped (2010)

Juli Baker and Bryce Loski live in different worlds. She lives on one side of the street, he on the other. Bryce, whose family is the picture of Eisenhower-era suburban respectability, learns from his father’s disdain that the Bakers aren’t; Juli is blissfully unaware either of the Loskis’ well-to-do-ness or of her own family’s hardships. They see each other every day from the time they are seven without ever really seeing each other.

The Flowers of St. Francis (1950)

Rossellini doesn’t cater to contemporary sensibilities by reinventing Francis as a mere eccentric free spirit, a medieval flower child, such as we find in Zefferelli’s Brother Sun, Sister Moon. Francis remains challenging to modern audiences here, his childlike spirit joined to insistence on strict religious obligation and ultimately to zeal for evangelization.

Flushed Away (2006)

If Flushed Away doesn’t reach the heights of demented genius of The Curse of the Were-Rabbit or even the lesser charms of Chicken Run, it’s still got a goofy inventiveness that puts it in the better half of this year’s crop of CGI films.

Footloose (2011)

The upshot is that this new Footloose is a dumbed-down, sexed-up take on a story that was already risqué and not too bright — one that shies away from the ’84 film’s critique of the church, but is also further from its lingering Christian worldview.

For Greater Glory (2012)

For Greater Glory tells a story of religious freedom and oppression that is far too little known, and that would be important and worthwhile at any time, but is strikingly apropos in our cultural moment.

For Greater Glory [video]

For Greater Glory in 60 seconds: my “Reel Faith” review.

Forbidden Planet (1956)

At once intelligent and campy, Forbidden Planet is an intriguing, perhaps overrated sci-fi classic that borrows plot points from Shakespeare’s The Tempest and strongly anticipates “Star Trek” in its sci-fi milieu — but its driving fears are the “monsters from the id,” the wayward, concupiscent passions of our own hearts.

The Forgotten (2004)

Recent

- Benoit Blanc goes to church: Mysteries and faith in Wake Up Dead Man

- Are there too many Jesus movies?

- Antidote to the digital revolution: Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality

- “Not I, But God”: Interview with Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality director Tim Moriarty

- Gunn’s Superman is silly and sincere, and that’s good. It could be smarter.

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.