Search Results

95 records found

The Apostle (1997)

A sensitive cultural ethnography of the exotic, much-maligned world of Southern Pentecostalism; a complex study of a character whose many contradictions startlingly combine sacred and profane dimensions; a spiritual exploration of the inscrutable workings of guilt and grace: The Apostle—long labored over by writer, director, producer, and star Robert Duvall—is all of these.

Apparitions at Fatima (1992)

Warner Bros’ The Miracle of Our Lady of Fatima may be better known, but Daniel Costelle’s 1992 Portuguese production Apparitions at Fatima is a more historically accurate and spiritually sensitive account of the visionary experiences of three young Portuguese children in 1917, culminating in the miracle of the sun witnessed by thousands.

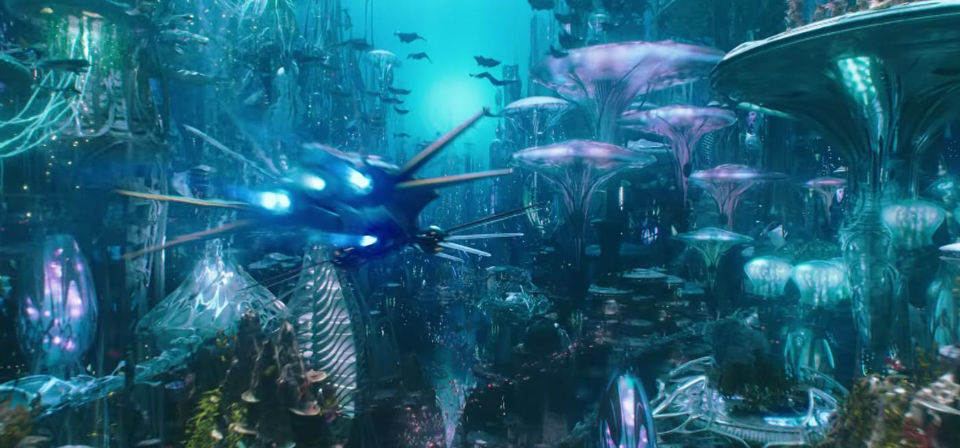

Aquaman (2018)

Like the Star Wars prequels, like James Cameron’s Avatar, it’s a movie with tons of problems, but it also contains images that made me catch my breath — gorgeous and even numinous sights I will remember forever.

Arctic Tale (2007)

Arctic Tale is co-presented by National Geographic Films, which released March of the Penguins, and Paramount Classics, which released An Inconvenient Truth, and when it grows up Arctic Tale would like to be both of those films.

Are the Borrowers thieves?!

Reader response to the lovely family film The Secret World of Arrietty, I’m delighted to say, has been almost entirely positive. However, I did receive one negative email from a reader who not only didn’t enjoy the film, but considered it downright immoral. Why? Because the Borrowers, tiny people who live in secret in big people’s homes, survive by “borrowing” (i.e., taking) the things they need from the big people.

Argo (2012)

The fact-based premise is almost enough to sell Argo by itself. Argo opens and closes as a tense political spy caper, but it’s also an affectionate send-up of the movie-making process. The old advice to writers to “write what you know” is applicable to movies about movies, from Singin’ in the Rain to The Artist, and few subjects inspire Hollywood — or appeal to movie fans and film critics — more reliably than Hollywood itself.

Armageddon (1998)

“Talk about the wrong stuff” is one officer’s disparaging comment as Willis’ team struts about NASA ostensibly preparing for their mission, hamming it up like class clowns in high school, ridiculing the process, flaunting their lack of couth like a badge of honor — all but letting their butt cracks stick out. Yes, in this film the honors science students are obliged to sit back and watch as the shop class saves the world.

Around the World in 80 Days (2004)

Without a doubt, the best thing about Frank Coraci’s Around the World in 80 Days is the fight scenes.

Arrival (2016)

In some ways it warrants comparison with Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, if only because Arrival achieves much of what I was hoping for from Interstellar.

![Arrival [video]](/uploads/articles/arrival.jpeg)

Arrival [video]

I try never to spoil anything, but honestly, just skip this video and go see it. I mean, then come back and watch the video, of course.

Arthur Christmas [video]

Here’s my 30-second take on Aardman Animation’s Arthur Christmas.

The Artist [video]

Here’s my 30-second take on The Artist.

The Ascension of the Lord: My favorite screen depiction

My favorite cinematic depiction of the Ascension of Jesus is one of the very first, from a very early silent film released 110 years ago.

Asghar Farhadi’s masterful A Hero: A decent man does the right thing, more or less

One of the things that makes Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi (A Separation) such a riveting storyteller is how persuasively he imagines sympathetic characters who are more or less trying to do the right thing finding the consequences of that “more or less,” that small bit of wiggle room, compounding and spiraling out of control in unforeseen directions.

The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007)

The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford is the best name for a western of any film in history. It’s the second half of the title that does it — the editorial moralizing, redolent of a 19th-century dime novel or monograph. The kind of thing that boys like young Bob Ford eagerly devoured in their beds at night as they dreamed of being daring and admired like Jesse James.

The Astronaut Farmer (2007)

Like the full-sized rocket in Charlie’s barn, the Polishes’ film looks every inch what it seems to be. It’s been compared to a Frank Capra film, though it lacks the dark undercurrent and comedic edge that give Capra’s films their heft and stature.

Atlantis (1991)

Loosely structured into thematic "chapters" such as "light," "rhythm," and "grace," accompanied by an ecclectic Eric Serra score, Atlantis is a documentary Fantasia, a poetic marriage of image and music (though the score, apart from an aria from Bellini’s La Sonnambula, lacks the pedigree of Disney’s masterpiece). Marred only by a brief opening voiceover, which muses pretentiously about man’s evolutionary origins in the ocean, Besson’s otherwise wordless film lets the beauty of the undersea world speak for itself.

Atlantis: The Lost Empire (2001)

Directors Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise (Beauty and the Beast) keep things moving fast enough to keep them from getting boring, and there are a few laughs along the way. Yet what could have made adequate summer entertainment for older kids and parents with low expectations is ultimately undone by pervasive echoes of New-Age pop spirituality and neopaganism in the film’s imagery and themes.

Au Hasard Balthazar (1966)

A stark, unsettling vision of human cruelty, folly, and destructive behavior, leavened by an icon of innocent suffering, Au Hasard Balthazar may be Robert Bresson’s most poetic, haunting, personal work — the culmination of the filmmaker’s style and concerns, the most "Bressonian" of films.

Au Revoir Les Enfants (1987)

Au Revoir Les Enfants, Louis Malle’s semi-autobiographical film about life in a Catholic boarding school for boys in Nazi-occupied France, has been called an elegy of innocence lost, though in fact the youthful characters are never truly innocent, only clueless, and what they lose is not innocence but something more elusive.

Recent

- Benoit Blanc goes to church: Mysteries and faith in Wake Up Dead Man

- Are there too many Jesus movies?

- Antidote to the digital revolution: Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality

- “Not I, But God”: Interview with Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality director Tim Moriarty

- Gunn’s Superman is silly and sincere, and that’s good. It could be smarter.

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.