Search Results

95 records found

American Beauty (1999)

Some movies have a moral. I say that as a mere statement of fact, with no implication that either having or not having a moral necessarily makes a movie better or worse. Some movies have a moral; American Beauty - and this is also a mere observation, not a value judgment - has an aesthetic.

An American in Paris (1953)

In a conceit both touching and surreal, Kelly plays an American ex-G.I. in Paris who’s never wanted anything but to paint, though he’s obviously the best hoofer in France.

An American mythology: Why Star Wars still matters

Star Wars is pop mythology — a "McMyth," as a recent critical article put it — but in our McCulture even a McMyth can be vastly preferable to no myth at all, and certainly to other, less wholesome mythologies (e.g., the Matrix trilogy). Even for those who generally prefer more traditional fare, there is still much to enjoy and appreciate in these half-baked, stunningly mounted fantasies of good and evil in a galaxy far, far away.

Amish Grace: Forgiving Our Enemies

Do I forgive the 9/11 terrorists? It’s a question I can’t remember asking myself before this week after screening the upcoming Lifetime TV movie Amish Grace. Inspired by the nonfiction book of the same name, the film is based on the real-life Amish school shooting in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania in the fall of 2006.

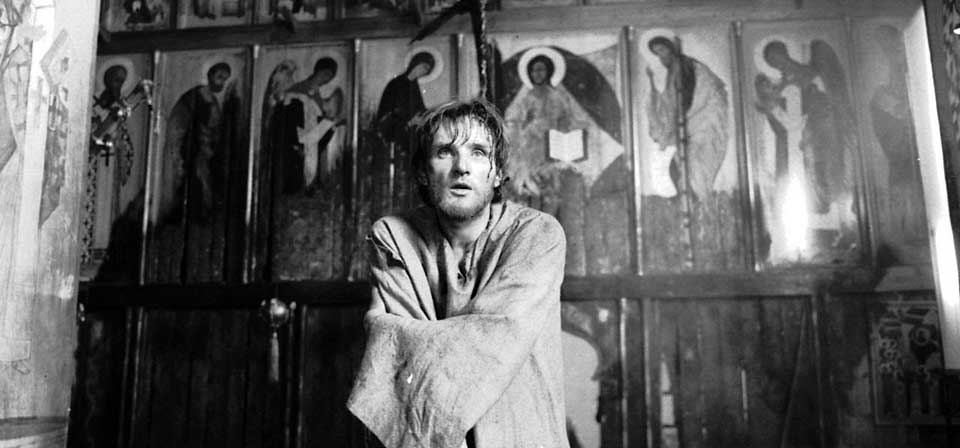

Andrei Rublev (1969)

The notion of art as a "religious experience" is sometimes bandied about too freely. Tarkovsky is one of a handful of filmmakers for whom this ideal was no cheap or desanctified metaphor, but literal truth.

Angels & Demons (2009)

Once you’ve established that your story is set in a world in which Jesus Christ is explicitly not God, and the Catholic religion is a known fraud perpetuated by murder and cover-ups, it sort of sucks the wind out of whatever story it was you were going to tell us next. Langdon could be ironing his chinos and helping little old ladies across the street, and it would still be set in that world, and those of us who care about such things will find it hard to bracket that and just go along with the thrill machine.

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

The Dead End Kids have dirty faces, all right — but they’re no angels. Tough-talking young hoods much given to slapping one another’s faces and terrorizing their lower East Side Manhattan neighborhood, they may tolerate sincere, savvy Father Jerry Connolly (Pat O’Brien) and his efforts to divert them from the dangers of life on the street; but it’s in Fr. Jerry’s boyhood chum, infamous gangster Rocky Sullivan (James Cagney), that the Kids find a mentor and kindred spirit.

The Animal (2001)

Funnier, perhaps, than anything in The Animal - which isn’t saying much - are the opportunities for critics to make "Survivor" jokes inspired by the presence of costar Colleen Haskell, the elfin-faced young thing who became a celebrity during the course of the CBS monster hit.

Animals are Beautiful People (1975)

Highlights include daredevil cartwheeling baboons, the remarkable partnership of the badger and the honey-guide bird, and the astonishingly intricate lengths to which the Kalahari bushmen go to find water. There’s a sequence with the animal residents of the fertile Kavango flood plains intoxicated on fermented fruit, and footage of an ostrich mating dance that strikingly resembles Fantasia’s animated ostrich ballet.

Anna Karenina [video]

Anna Karenina in 60 seconds: my “Reel Faith” review.

![Annie [video]](/uploads/articles/annie-2014.jpg)

Annie [video] (2014)

I want to say I love the idea for Little Orphan Hushpuppy … but I’m not convinced there’s actually an idea here.

Announcement: Where I’ll Be and What I’ll Be Doing

Everything is always changing, but August 2012 will go down as a month of particularly momentous milestones for the Greydanus family—some of which will have repercussions on my life and work, including my film review work, for many years to come.

Another Decent Films Mail Double Dip!

What, already? It was only the beginning of Lent that the last two mailbags went up — and now, here in time for Easter Week, are the next two, Mailbag #18 and Mailbag #19. (Unfortunately the RSS feed still isn’t picking up the Mail columns, so for RSS readers, this blog post is your heads up. Hopefully it’ll be fixed soon.)

Ant-Man (2015)

Three years ago, when Marvel first announced that Ant-Man would be getting his own movie, I tweeted, “I don’t care how much money Avengers makes. The world does not need an Ant-Man movie.” Ant-Man, I felt, was too minor a hero, too obscure and inconsequential — in a word, too small — to warrant the big-screen Marvel movie treatment.

Ant-Man and the Wasp (2018)

In some ways Ant-Man and the Wasp is the kind of movie I wanted Ant-Man to be: namely, a refreshing antidote to the rest of the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

![Ant-Man and the Wasp [video]](/uploads/articles/anttmanandthewasp-vid.jpeg)

Ant-Man and the Wasp [video] (2018)

No infinity. No war. (Almost.) Why can’t more Marvel movies be like this?

The apocalypse will be televised

“Not with a bang but with a whimper” was T. S. Eliot’s revisionist idea of the world’s end in The Hollow Men. He was almost right. Not with a whimper, but with a million whimpers, each more feeble and bathetic than the last, is the way we seem to be slouching toward oblivion.

Apocalypto (2006)

Gibson is a consummate filmmaker, and the action is never less than riveting. Yet as the film repeatedly ratchets up the wince factor beyond what seems necessary or appropriate, it’s hard not to feel that suffering has been reduced to spectacle.

Apollo 13 (1995)

In an age when we rely on computerized directions and GPS devices to drive to the next town, it seems an almost mythic scenario: brilliant men calculating outer-space trajectories on the fly with pencils and slide rules, keeping life and limb together literally with duct tape, flying to the moon and back simply because they could.

Apostasy, ambiguity and Silence

Shusaku Endo’s 1966 novel Silence honors 17th-century Japanese martyrs who sang hymns as they succumbed slowly to grueling deaths. But it also empathizes with, perhaps even exonerates, many who capitulated to official demands for ritual renunciations of Christian faith — typically trampling on images of Jesus or Mary, called fumie, designated for this purpose.

Recent

- Benoit Blanc goes to church: Mysteries and faith in Wake Up Dead Man

- Are there too many Jesus movies?

- Antidote to the digital revolution: Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality

- “Not I, But God”: Interview with Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality director Tim Moriarty

- Gunn’s Superman is silly and sincere, and that’s good. It could be smarter.

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.