Reviews

Pixels (2015)

The idea of saving the world from alien invaders with classic video-game skills is not without a certain dumb appeal.

Ant-Man (2015)

Three years ago, when Marvel first announced that Ant-Man would be getting his own movie, I tweeted, “I don’t care how much money Avengers makes. The world does not need an Ant-Man movie.” Ant-Man, I felt, was too minor a hero, too obscure and inconsequential — in a word, too small — to warrant the big-screen Marvel movie treatment.

Minions (2015)

Like the Penguins of Madagascar and Mater the tow truck, the Tic-Tac-shaped, banana-colored Minions join the ranks of popular comic sidekicks who have taken over their animated franchises. This is usually a sign of the end, although Cars 3 is on the way, and nobody has said Madagascar 4 isn’t happening.

Batkid Begins (2015)

Above all, it’s the story of the incredible lengths to which the Make-a-Wish staff and volunteers go in order to create special experiences for long-suffering children to make up in some way for their lost childhood.

Inside Out (2015)

Inside Out is a rare family film for so many reasons: a story with no villain, for one thing, centering on an imperfect but basically happy intact family going through a tough time. It is a wise and wounding depiction of growing up, a story of growth and loss, with real stakes and real consequences.

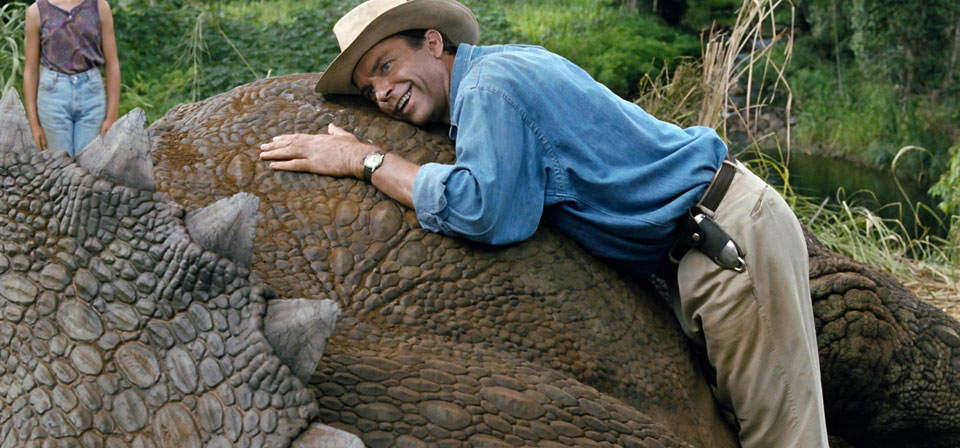

Jurassic World (2015)

Pratt more than delivers. You could almost say he manages to stand in for Sam Neill, Jeff Goldblum and Laura Dern. He’s got Neill’s toughness, Goldblum’s humor and Dern’s down-to-earthness. His character, Owen Grady, is Jurassic World’s velociraptor trainer, and in a terrific early set piece Pratt persuades me that he’s capable of standing up to three raptors armed with nothing but charisma and nerve.

Jurassic Park (1993)

In the twenty-odd years since Jurassic Park pioneered the use of photorealistic computer-animated living creatures integrated into a live-action film, computer animation has become even more prevalent. Yet in all that time, it’s hard to think of a single blockbuster spectacle that uses computer imagery to achieve a similar sense of awe and grandeur.

Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)

In the first act of Mad Max: Fury Road, Tom Hardy’s Max spends more time than you might expect strapped helplessly to the front of a turbo-charged Chevy coupe, maniacally driven by a fanatic through a hellish landscape, an unwilling witness to the chaos ensuing around him. Sitting in the theater, I felt about the same way, I think.

Tomorrowland (2015)

Tomorrowland argues that the future is as dark or as bright as we choose to make it; that artists, scientists and dreamers can save the world; that the dystopian post-apocalyptic nightmares dominating popular culture are killing us, and are no more inevitable or realistic than the Space-Age techno-optimism of Disney’s Tomorrowland and EPCOT, Roddenberry-era Star Trek and even The Jetsons.

The Sound of Music (1965)

Half a century later, The Sound of Music is probably still the world’s favorite big-screen stage musical adaptation. Joyous, gorgeous, comforting, full of (almost) uniformly spectacular songs, the film’s emotional power is irresistible, even for the many critics, such as Pauline Kael, who hated its shallowness and emotional manipulation.

Make Way for Tomorrow (1937)

Any time I run across a list of movies people probably haven’t seen but should, one title I look for is the Catholic director Leo McCarey’s forgotten humanist masterpiece Make Way for Tomorrow.

Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015)

The first word of dialogue spoken by an Avenger in Avengers: Age of Ultron, from Iron Man (Robert Downey Jr.), is a rude expletive. The second word, from Captain America (Chris Evans), is a mild rebuke. In two words of dialogue, writer-director Joss Whedon gives us characterization, conflict and theme.

Sullivan’s Travels (1941)

The comic genius Preston Sturges believed that laughter is the best medicine, and that what people in hard times want is to forget their troubles and escape for 90 minutes or so into a world of lighthearted comedy, snappy repartee and slapstick silliness.

Two Days, One Night (2014)

It is about self-interest and empathy, practical necessities and moral choices. It’s about the importance of work and the ruthlessness of economics based purely on self-interest and competition. I can think of no film that more persuasively or powerfully illustrates in human terms what popes from Leo XIII to Francis have been talking about for over a century regarding the dangers of pure capitalism unrestrained by moral concerns.

Song of the Sea (2014)

Like Miyazaki, Tomm Moore isn’t afraid to take the time to breathe deeply, savor moments of silence and beauty, and open the door to wonder and mystery.

Cinderella (2015)

Kenneth Branagh’s Cinderella is such a gallant anachronism, such a grandly unreconstructed throwback, that it offers, without ever raising its voice, a ringing cross-examination of our whole era of dark, gritty fairy-tale revisionism.

Watership Down (1978)

Newly remastered for Blu-ray and DVD, the classic animated adaptation of Richard Adams’ beloved tale is available from Criterion.

The Overnighters (2014)

Jesse Moss’s The Overnighters is an existentially probing documentary with more layers than a twisty Hollywood thriller, at turns inspiring, challenging, sobering and finally devastating.

Selma (2014)

Selma achieves something few historical films do: It captures a sense of events unfolding in the present tense, in a political and cultural climate as complex, multifaceted and undetermined as the times we live in.

Unbroken (2014)

Angelina Jolie’s Unbroken is an honorable movie about an inspiring true story. It is impeccably crafted, with a raft of remarkably talented people behind it. It is a celebration of the old-fashioned virtues of duty, grit, fortitude and honor. In the end, it tips its hat to faith, forgiveness and reconciliation. The film I just described is a film that, on paper, I should love.

Recent

- Crisis of meaning, part 3: What lies beyond the Spider-Verse?

- Crisis of meaning, part 2: The lie at the end of the MCU multiverse

- Crisis of Meaning on Infinite Earths, part 1: The multiverse and superhero movies

- Two things I wish George Miller had done differently in Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga

- Furiosa tells the story of a world (almost) without hope

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.