Reviews

K-19: The Widowmaker (2002)

Unfortunately, these novel elements are tied to a human conflict between two antagonistic captains (Harrison Ford and Liam Neeson) that is not only hackneyed and uninvolving, but morally simplistic and finally flat-out insulting. It’s hard to be unmoved by what the men of the K-19 go through, but it’s equally hard to overlook the glaring flaws in the human drama — especially when the latter is directly related to the former. As an exercise in logistics and adversity, K-19 is compelling, but as a story about human decisions and moral issues, it’s full of holes and clichés.

Men in Black II (2002)

Beyond more action and bigger effects, the sequel brings nothing new to the table. You’ll wait in vain for satirical "revelations" about the presence of aliens among us to match the wit of the jokes in the original about cab drivers or the World’s Fair. Instead, we get limp gags like the one about the Post Office being staffed by aliens. (Why? Is it a joke about postal efficiency? The "going postal" stereotype? The fact that they make rounds? What?)

Stuart Little 2 (2002)

Remarkably, Stuart Little 2 manages to be both more satisfying for adults and more kid-friendly than the original. Older viewers will appreciate the sequel’s stronger story and witty script; and even little kids who might have found the original film’s menacing Central Park gangster cats too intense may be able to watch this film’s villainous falcon without fear of bad dreams.

American Beauty (1999)

Some movies have a moral. I say that as a mere statement of fact, with no implication that either having or not having a moral necessarily makes a movie better or worse. Some movies have a moral; American Beauty - and this is also a mere observation, not a value judgment - has an aesthetic.

Dragonfly (2002)

Dragonfly is a ghost story of sorts, but it isn’t a horror film (though it occasionally thinks it is). The ghost seems to be the late wife of Dr. Joe Darrow (Kevin Costner); and who would be frightened of his own best beloved, even if she happened to be a ghost?

Lilo & Stitch (2002)

Lilo & Stitch is a unique imaginative achievement that succeeds in its own right, without laying down any kind of template for future films to follow. Attempts to repeat its success, to make it into a formula, would be a dismal failure, unless perhaps the formula were to be "Give the creative people room to try something new and let them work without a safety net." What a concept.

Minority Report (2002)

Spielberg has always known how to manipulate an audience’s emotions, a knack he makes effective use of here. Humor alternates with squirming discomfort and emotional release as the director pokes fun of Cruise’s sex-symbol status in a couple of funny incidents, then leaves us wincing with a number of scenes involving eyeballs, or a character fumbling blindly for the one edible sandwich in a squalid refrigerator.

Road to Perdition (2002)

I enjoyed looking at Road to Perdition, but I didn’t especially enjoy watching it.

Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

The Empire Strikes Back is the backbone of the Star Wars saga. It takes the story and themes of the first film into deeper waters.

Bad Company (2002)

The first hour works quite a bit better than the second hour, in part because there is a second hour. The setup: When CIA agent Kevin Pope (Rock) is murdered in the middle of an important undercover operation involving the black-market sale of a miniature thermonuclear device, Pope’s CIA mentor Gaylord Oakes (Hopkins) must convince the sellers that Pope (or rather his undercover persona) is still alive. To do this, Oakes must turn to — you guessed it — Pope’s long-lost twin brother.

The Bourne Identity (2002)

Like the memory-impaired antihero of Memento, the protagonist of Doug Liman’s The Bourne Identity (and a trilogy of Robert Ludlum novels before that) has no choice but to trust himself even though he can’t be sure he’s a trustworthy individual. Perhaps his honorable aspirations themselves are a good sign. Certainly the amazing abilities and instincts that suddenly surface when needed are clues to who and what he is. Jason may not know much, but he’s pretty sure he’s something out of the ordinary.

Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood (2002)

Despite being more of the "Yo" than "Ya" persuasion, I think I’m pretty receptive toward what are commonly called "chick flicks." After all, my wife and I enjoy the same "guy movies"; why shouldn’t we enjoy the same romances and other female-targeted films?

Star Wars [Episode IV – A New Hope] (1977)

(Review by Jimmy Akin) Like earlier pulp films, Star Wars draws on mythic and fairy-tale archetypes: a young orphan-hero; a mysterious wizard-mentor; a fearsome dark lord; a magical sword; a princess held prisoner; a gallant rescue mission. Yet on a deeper level, Star Wars is more convincing as a myth or fairy tale in its own right.

The Sum of All Fears (2002)

Though constructed as an action-oriented thriller, the film’s centerpiece is a wrenching glimpse of a scenario that may be in our nation’s future, depicted in a way that’s neither sensationalized nor minimized.

Insomnia (2002)

Daylight floods Dormer’s life, relentless, ubiquitous — like the penetrating glare of the ongoing Internal Affairs probe back in LA, where Dormer may or may not have something to hide. Like the searching gaze of Alaskan local cop Ellie Burr (Hilary Swank) as she investigates Dormer’s account of a second killing that occurs when an attempt to catch the killer goes tragically awry. Like "the eye of God that will not blink," as Roger Ebert describes the Arctic Circle’s midnight sun in his review of the original film.

Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron (2002)

A strangely grim indoctrination into the politics of victimization, Spirit apparently expects kids to slog willingly through scene after scene of this stuff, not because it’s all such fun to watch, but because the filmmakers are so sure it’s Good For You.

The Salton Sea (2002)

This is not a thought Tom takes to heart. Nor is it one he struggles with, or indeed ever thinks about again. The quest for revenge is at the heart of The Salton Sea, and although in this one scene the film fleetingly acknowledges the possibility of an alternative to bitterness and hatred, it’s not in the context of any larger interest in or exploration of the moral issues.

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000)

The story is said to be set in 19th-century China, but its roots are older, reaching for a mythic age of larger-than-life heroes and superhuman derring-do. Heroes with paranormal abilities were also a theme of the recent Unbreakable; but Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon has what was lacking in Unbreakable: a sense of wonder, of exhilaration, of mystery and beauty and hope.

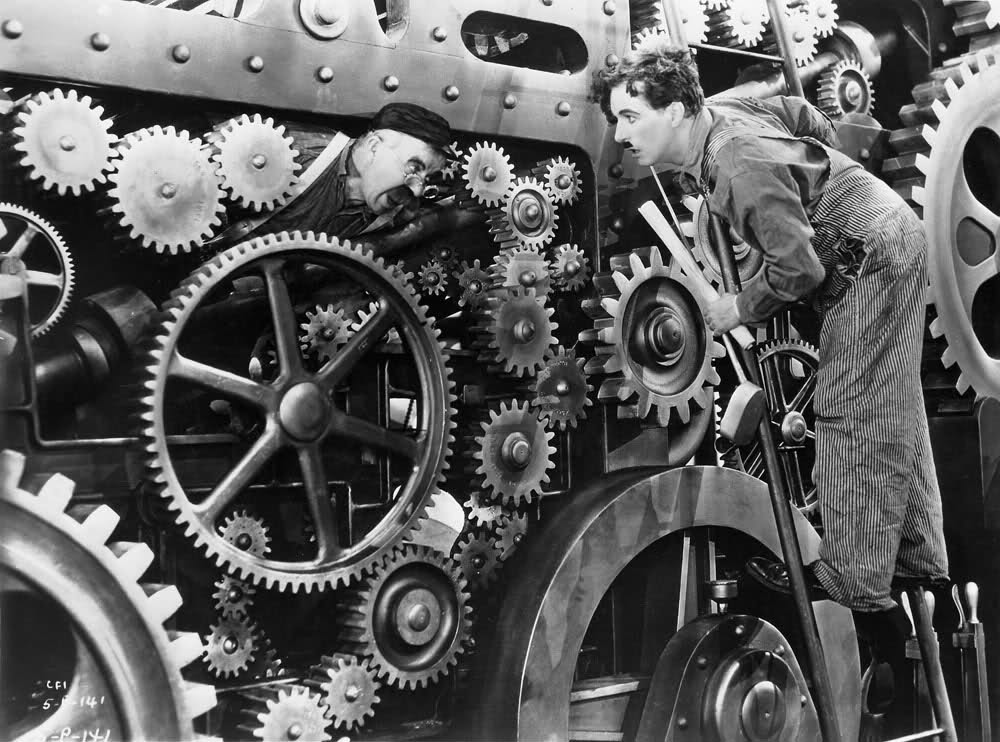

Modern Times (1936)

Silent films were already old-fashioned and out of vogue in 1936 when Charlie Chaplin completed his last silent feature film, Modern Times, almost ten years after the sound revolution began with The Jazz Singer. A silent film consciously made for the sound era, Modern Times is a comic masterpiece that remains approachable today even for movie lovers raised on computer imaging and surround sound.

High Crimes (2002)

Only Jim Caviezel (The Count of Monte Cristo; Frequency) brings anything new to the table, displaying even more range and subtlety than in his recent starring turn in The Count of Monte Cristo. Other than his performance, High Crimes holds few surprises.

Recent

- Benoit Blanc goes to church: Mysteries and faith in Wake Up Dead Man

- Are there too many Jesus movies?

- Antidote to the digital revolution: Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality

- “Not I, But God”: Interview with Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality director Tim Moriarty

- Gunn’s Superman is silly and sincere, and that’s good. It could be smarter.

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.