Solaris (2002)

Solaris comes originally from the pen of Polish science-fiction writer Stanislaw Lem, an atheist and apparently a one-time friend of Karol Wojtyla, the future Pope John Paul II, with whom Lem used to drink coffee and argue about God.

Caveat Spectator

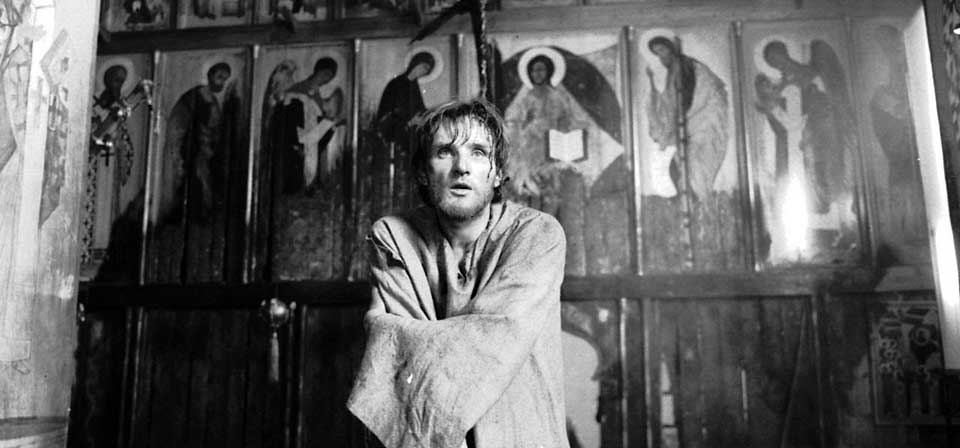

Recurring depictions of and references to suicide and killing; depictions of sexuality with brief rear nudity; references to abortion; minimal profanity and coarse language; anti-theistic comments.Solaris was first adapted for the screen in 1972 by acclaimed Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky, whose Andrei Rublev is one of the fifteen films named on the Vatican film list for outstanding religious value. Lem himself was most unhappy with the resulting film, resenting its stylistic "weirdness," its almost total lack of interest in the scientific underpinnings of his novel, and, significantly, its affirmation of the very human emotions and values that his novel had sought to deconstruct. Yet along with 2001: A Space Odyssey, Tarkovsky’s Solaris is among of the most celebrated — and confounding — science-fiction films of all time.

This year’s Solaris from writer-director Steven Soderbergh (Erin Brockovich is part of an ongoing trend toward science fiction aspiring to the tradition of 2001. Not long ago, science fiction had become a wasteland of forgettable, mindless action flicks. The year 2000, for example, gave us Red Planet, Battlefield Earth, The 6th Day, Hollow Man, Pitch Black, and Supernova (as well as Mission to Mars, which didn’t fit the mindless-action pattern but managed to be lame anyway). Even the previous year’s The Matrix was notable primarily for its kinetic impact and craft; the story, though clever, was long on allusions and short on genuine resonance.

In the last eighteen months, however, there’s been a trend toward more thoughtful and ambitious science fiction, sometimes seriously flawed, but far more intriguing than the dumb action that preceded it. Not that we’ve stopped getting pictures like The Time Machine and Imposter; but there’ve also been challenging films from the likes of Steven Spielberg, Cameron Crowe, and M. Night Shymalan: A.I. Artificial Intelligence, Vanilla Sky, Minority Report, Signs, and now Solaris.

Whether one likes or dislikes these movies, and for the record I wasn’t a fan of Vanilla Sky or even Signs — and I don’t like Solaris a whole lot more — this is a hopeful trend.

Like Vanilla Sky, Solaris is a remake of a celebrated foreign film, adapted by a hot young American writer-director and starring a major male screen idol (in this case George Clooney), with a "Twilight Zone" atmosphere and similar devices and themes: a dead beloved who seemingly returns to life; blurring of reality and illusion; the relationship of memory and identity; solipsism and the problem of other selves.

Yet, unlike Vanilla Sky, Solaris doesn’t cheat with the rules of its own universe, and it doesn’t tack on tidy explanations clearing everything up in deference to mainstream American expectations.

Solaris also resembles Signs in its story of a grieving widower whose encounter with alien forces compels him to come to terms with his grief and guilt; yet it avoids the superficial cleverness and pat ease with which that film tied together all its loose ends. (As one character says, "There are no answers… only choices.")

Because of its deliberate pacing and elusive narrative style, some viewers will find Solaris difficult or dull. My complaint is different: I think it’s dishonest. (Spoilers follow.)

In each of its three incarnations, Solaris is about a place where human beings encounter other people who can’t possibly be there. Dead spouses, siblings, children simply show up on a lone spaceship orbiting the mysterious planet Solaris. They can’t be real, yet they act and feel real, they seem acutely self-aware, and it seems wrong to treat them as illusions or phantoms. As with the "mecha" boy played by Haley Joel Osment in A.I., it seems impossible to know how to feel or even to act toward these "guests."

In the original novel, Lem used this premise, as far as I can tell, to deconstruct human feelings of love and individuality, which he saw as having no larger meaning or validity in the teeth of the implacable incomprehensibility of the universe. Tarkovsky, on the other hand, used the same premise to explore how new circumstances might give rise to new moral situations and realities, while also affirming existing human values and attachments.

But Soderbergh seems to have taken the premise as a romance of second chances and redemption, of opportunity to make up for the wrongs of the past. He wants to know if we would be doomed to make the same mistakes again and again with the same people, or if we might be able to do things differently a second time.

Like his protagonist Kelvin (Clooney), Soderbergh seems ultimately to have concluded that it doesn’t matter whether the "guests" are "real" or not (that they’re "real to us," or some such thing, and that’s all that matters. In fact, the movie questions whether we ourselves have a reality of a different sort, or are only "puppets" convinced we’re something more. Is the perception or experience of selfness or personhood in the world of Solaris all there is, whether that of another, or even of ourselves?

(Further spoilers.) Does Solaris have a happy ending? As with the ending of A.I., it’s a matter of interpretation. With both films, if the ending is understood as intended to be a feel-good sentimental sop to the viewer, then it becomes profoundly disturbing and anti-humanistic. Only if it’s understood as intended to strike a chord of dread and emptiness is it possible to regard it as in any way positive.

I can’t be sure how Soderbergh meant his ending, any more than I can be of Spielberg. But I have a suspicion in the case of Solaris that it isn’t meant to be dreadful and empty.

Related

The Sacrifice (1986)

To “rip open the inconsolable secret,” to awaken the spiritual hunger for something beyond the materialistic scope of our fragmented, desacrilized modern existence, was the burden of Andrei Tarkovsky, cinematic poet laureate of the Russian soul.

Andrei Rublev (1969)

The notion of art as a "religious experience" is sometimes bandied about too freely. Tarkovsky is one of a handful of filmmakers for whom this ideal was no cheap or desanctified metaphor, but literal truth.

Recent

- Benoit Blanc goes to church: Mysteries and faith in Wake Up Dead Man

- Are there too many Jesus movies?

- Antidote to the digital revolution: Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality

- “Not I, But God”: Interview with Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality director Tim Moriarty

- Gunn’s Superman is silly and sincere, and that’s good. It could be smarter.

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.