Aladdin (2019)

Aladdin is fine. Everything’s fine. How could it be otherwise? It’s the story you know already, almost exactly. They say the lines and sing the songs, the same songs, almost exactly. It’s a good story and they’re good songs. There are no spoilers in this review because how could there be?

When you take your kids to Disneyland and they stand in line to meet Aladdin and Princess Jasmine, they want to recognize them when they get to the front of the line. If they had Mena Massoud and Naomi Scott at Disneyland playing Aladdin and Jasmine, the kids would be thrilled. They would be puzzled, on the other hand, by soft-spoken Marwan Kenzari in the role of Jafar, the treacherous Grand Vizier, and Jasmine’s father, the ridiculous, roly-poly Sultan, played by distinguished Navid Negahban.

Caveat Spectator

Moderate fantasy action and menace.Egyptian-born Massoud’s wry grin suits diamond-in-the-rough street-rat Aladdin, who will acquire the magic lamp and win the princess’ heart. Scott, a British actress whose mother is from India, blends regal dignity with fierceness in a role that tries to be more feminist than the story allows. (Massoud is an observant Coptic Christian; Scott’s parents co-pastor an evangelical church in London.) Massoud and Scott lead an ethnically diverse cast making up the multicultural world of Agrabah, here a vaguely Middle Eastern port city with South Asian and other regional flavors. Kenzari’s Jafar is less a traditional Disney icon of evil than a quietly ambitious schemer with an inferiority complex, a social climber who has risen from origins as humble as Aladdin’s, believing that you’re either the most powerful man in the room or you’re nothing.

Are deeply resonant male voices simply out of style? Watch both versions of The Jungle Book and compare the Baloos (Bill Murray vs. the inimitable Phil Harris) or the Bagheeras (Ben Kingsley, no slouch certainly, vs. Sebastian Cabot, with his rich, gravelly line readings). Compare Luke Evans’ Gaston to opera singer Richard White in the original Beauty and the Beast. For over a quarter century, not only in the original cartoon but also on stage, on ice and in video games and other screen versions, Jonathan Freeman’s sinuous baritone and crisp diction have defined the villainy of Jafar. Kenzari’s voice is similar in pitch to Brendan Gleeson’s, and while Gleeson can certainly play villainous, his energy is about as unlike Jafar’s as his physique.

“One Jump Ahead,” the first big production number, with guards chasing thieving Aladdin through the bazaar, was director Guy Ritchie’s best opportunity to shine, since it’s an action sequence as well as a musical number. It’s also the most improvable musical sequence in the original. When I first saw Aladdin in 1992, I had never heard of parkour or Jackie Chan, but I knew I wanted the action here to be something more special — to be clever, not just fast. There’s some parkour in Ritchie’s “One Jump Ahead,” but it’s ruined the way most modern action is ruined, by close-ups and quick cuts that suggest action without the bother of staging and filming it well.

Later sequences are similarly unkind to the dance choreography. Did anyone consider going full Bollywood and showing American audiences a less familiar approach to song and dance? How about letting Will Smith bring some Fresh Prince style to the musical numbers? Anything to give this movie a reason to exist beyond the cash grab? Actually, it seems the answer is yes, yet they chose — deliberately — to put Smith rapping over the most Bollywood dance sequence only at the very end, after the movie is over.

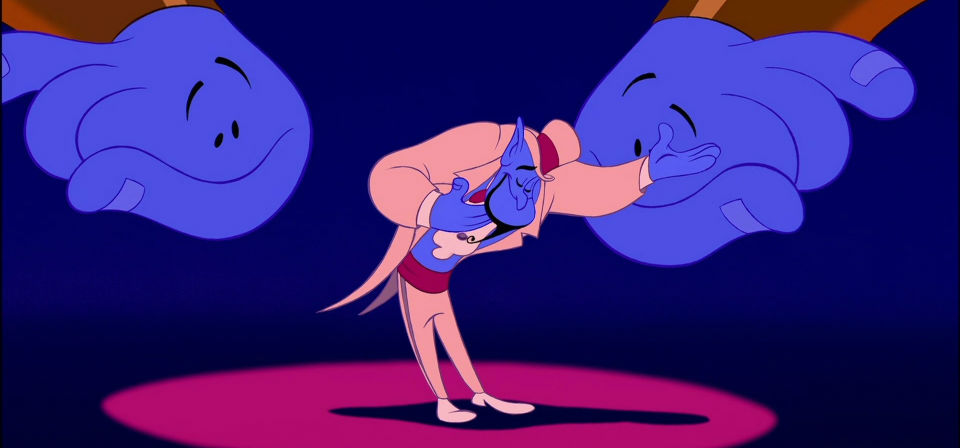

Which brings us to the big blue elephant in the room. One of the pleasures of the cartoon Aladdin is watching the animators’ shot-by-shot struggle to keep up with Robin Williams’ lightning-like delivery and quicksilver character changes. As Fantasia sought to portray the splendor of classical music visually, the Aladdin animators tried to render Williams’ mercurial genius in ink and paint. In a way, everyone involved in this new Aladdin is still trying to keep up with Williams … which, of course, is the problem.

This is not to diss Smith, a multitalented and charismatic performer whose outsize personality is more than up to the role of a genie. To his credit, Smith isn’t trying to compete with Williams, except he has to say a lot of the same lines and sing a lot of the same lyrics. And he’s blue, and his upper body (CGI-enhanced muscles and all) fades into a blue vapor trail, except when he’s passing as human, which he does more here than in the cartoon. The computer-effects team work gamely to give Smith something of the physical fluidity of his animated predecessor, but without Williams’ verbal virtuosity — and the magic of old-fashioned 2-D hand-drawn animation — it’s all just a dim reminder of the superiority of the original.

Like Bill Condon’s Beauty and the Beast and, all too probably, Jon Favreau’s upcoming The Lion King, Aladdin suffers from trying to follow too closely in the footsteps of a Disney Renaissance classic that is also a Broadway musical, a sacred text to the young parents who grew up with it and whose kids know it by heart. The story of Aladdin from One Thousand and One Nights, like the story of Cinderella, The Jungle Book and for that matter Beauty and the Beast, is bigger than one Disney cartoon. The makers of the new Cinderella and Jungle Book movies knew and cared about this. With Cinderella, it probably helped that there have been many cinematic versions over the years. The goal wasn’t just to remake a cartoon, but to make a “definitive Cinderella for generations to come,” a film that would be “one for the time capsule,” in the words of Disney creative chief and co-chairman Alan Barr. With The Jungle Book, screenwriter Justin Marks went back to Kipling to enrich the story with textures and details beyond the cartoon: the Peace Rock and the Water Truce; the jungle creation myth and the semi-religious reverence for elephants, and so forth.

I can’t swear that no one involved in Aladdin cracked a copy of One Thousand and One Nights — or for that matter took a second look at the 1940 The Thief of Bagdad, a major influence on the 1992 Aladdin — but what would be the point? The 1992 film is the only text that matters now. Anyway, Ritchie made a King Arthur movie, and there’s no evidence that he or anyone else involved read anything about King Arthur.

Did you know that in One Thousand and One Nights the princess kills the evil sorcerer? If they wanted Jasmine to be more empowered, giving her an active role in defeating Jafar would have been a fresh move. Fresher, certainly, than a few politically correct tweaks, like giving her aspirations of reigning as sultan in her own right and a new girl-power ballad that, as robust as Scott’s pipes are, goes nowhere dramatically. (Jasmine does make a speech that briefly turns the tide until Jafar’s next power move. The movie throws in some rhetoric about the common people of Agrabah but has no real interest in them.) I do appreciate that Jafar has no romantic designs on Jasmine, except as an afterthought, as a way of humiliating the sultan.

Perhaps the single biggest blunder (okay, I lied; this is a spoiler) is letting Jasmine actually swipe the lamp from Jafar, leading to a big chase sequence in which the heroes alternately lose and recover the lamp — and not once, while they have it in their hands, do they rub it and wish Jafar defeated. I know they’re busy, but really.

Theological caveat: On more than one occasion the Genie is called “the most powerful being in the universe.” Did it occur to no one that this line might not fly in the Middle East as well as middle America? I mean, I’m perfectly happy to bust out Aquinas and explain to my kids why God is not a being, but not for this movie.

Related

Aladdin (1992)

Disney’s Aladdin does more than give Williams an opportunity to let loose the comic giant inside him: It offers the Disney animators perhaps their greatest creative challenge, and inspiration, in over half a century.

Recent

- Benoit Blanc goes to church: Mysteries and faith in Wake Up Dead Man

- Are there too many Jesus movies?

- Antidote to the digital revolution: Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality

- “Not I, But God”: Interview with Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality director Tim Moriarty

- Gunn’s Superman is silly and sincere, and that’s good. It could be smarter.

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.