Articles

An American mythology: Why Star Wars still matters

Star Wars is pop mythology — a "McMyth," as a recent critical article put it — but in our McCulture even a McMyth can be vastly preferable to no myth at all, and certainly to other, less wholesome mythologies (e.g., the Matrix trilogy). Even for those who generally prefer more traditional fare, there is still much to enjoy and appreciate in these half-baked, stunningly mounted fantasies of good and evil in a galaxy far, far away.

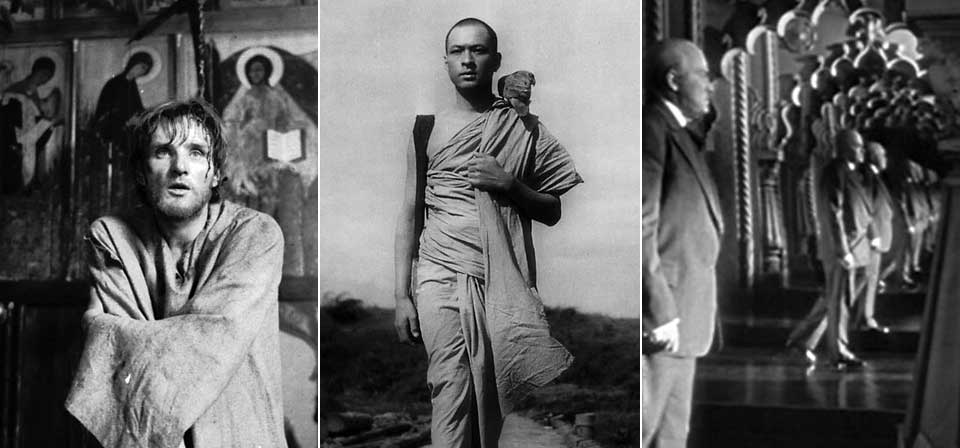

The Vatican Film List

The pope’s remarks were both forward looking, speaking to the potential of cinema to become “a more and more positive factor in the development of individuals and a stimulus for the conscience of society as a whole,” and also historically minded, speaking positively of the praiseworthy contributions of “many worthwhile productions during the first hundred years of [the cinema’s] existence.”

2004: The year in reviews

Did anything worth caring about come to cineplex screens? Anything anyone will be talking about or revisiting five or ten years from now?

Triple Threat: Fox’s Spring 2005 Family Film Lineup

Typically, the spring movie season has at most one decent film for family audiences. Last year it was Two Brothers; offerings from previous years included Holes (2003), Ice Age (2002), Spy Kids (2001), and The Emperor’s New Groove (2000).

2003: The year in reviews

It was a rough year at the movies for the Catholic Church.

Faith and Film in the Post-Passion Era

Constantine might sound like the latest entry in Hollywood’s string of violent costume dramas (Alexander, Troy, King Arthur), but it’s not actually about the Roman emperor who was the subject of such religious films as Constantine and the Cross. In this film, instead of a sign in the sky, the cross is a weapon in the ero’s hands. Starring Keanu Reeves, Constantine is a sort of a cross between Hellboy and The Exorcist with some Matrix attitude thrown in, a violent R-rated action-thriller of the supernatural based on the DC/Vertigo comic book Hellblazer, about a cynical demon-hunter antihero who’s literally been to hell and back. Though he knows that what God expects is belief, self-sacrifice, and repentance, he is futilely trying to earn his way into God’s good graces.

Sports and Coaching, Life and Death: Coach Carter & Million Dollar Baby

Coach Carter is based on the real-life story of Ken Carter, an uncompromising high-school basketball coach at a tough urban school who requires more from his players than great basketball. He insists that they sign contracts requiring them to attend classes, sit in the front row, and maintain a C-plus grade point average or better — and is willing to lock the gym and forfeits games if they fall behind in their classes.

The Kinsey controversy

The life and work of Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey, the Indiana University entomologist turned pioneering sexologist, has provoked accounts and interpretations as divergent, and as bitterly contested, as John Kerry’s Vietnam service in the last election. And, while it’s true that Kinsey’s work warrants such scrutiny, it’s also true that this only makes the task of weeding through the arguments more daunting.

“Pick The Right One to be in the Foxhole With”

It’s not just a buzzword, either. There’s a special hand gesture that goes along with it. First you hold your hands up, palms outward, fingers spread apart. This where we are: no synergy. Then you clasp your hands into fists with the tips of the fingers of each hand inside the fist of the other hand, so that your hands make a sort of "S" shape. This is where we need to get to: synergy. Get it? (If you think this kind of thing doesn’t really pass for deep thought in corporate convention halls and conference rooms, you don’t know corporate America.)

Joy to the World: A Christmas Carol and the attack on — and defense of — Christmas

Scrooge’s conversion, like many conversions, is just such a dramatic revelation out of crisis, "as sudden as the conversion of a man at a Salvation Army meeting," says Chesterton, adding slyly, "It is true that the man at the Salvation Army meeting would probably be converted from the punch bowl; whereas Scrooge was converted to it. That only means that Scrooge and Dickens represented a higher and more historic Christianity" ("Christmas Books").

“I get so frustrated with Hollywood”: Paul Feig on I Am David

It isn’t only Jim Caviezel, the Christ of The Passion, here another nobly self-sacrificial prisoner who freely allows himself to be wrongly condemned in order to save another. It’s also the actor who plays the complex, conflicted official who suspects his prisoner is innocent but must pass judgment anyway — Pontius Pilate in The Passion, "The Man" in I Am David. In both films, the role went to Bulgarian actor Hristo Shopov.

Jackie Chan: An Appreciation

The fact is, Jackie’s appeal is hard to sum up in a single sentence. Ask five different Jackie Chan fans what they like about him, and you may get five different answers.

Understanding the Catholic Meaning of The Passion of the Christ

In its most extreme form, the charge of morbidity has been laid at the feet of the Christian faith itself. Christianity’s harshest critics denounce it as "a religion of death." Clearly, at some point objections of this sort must be regarded as a case in point of what the scriptures call the "scandal" of the cross. It is the cross itself, the very suffering and dying of God made man, and the way Christians respond to this event in their faith and devotion, that is behind much (though again not all) of the religious and anti-religious controversy over the brutality of this particular film.

The Incredibles: Big fish in a depleted pond

Let’s face it: So far, it’s been a lousy year for family films. Until now, the fine Two Brothers has been just about the only bright spot. Of course DreamWorks’ phonetically similar CGI twins Shrek 2 and Shark Tale each made far more money than Two Brothers, but neither is quite what I consider fine family viewing. And other choices have been forgettable and quickly forgotten: Home on the Range, Clifford’s Really Big Movie, Good Boy!

The Cross and the Vampire: Religious Themes in Terence Fisher’s Hammer Horrors

The religious themes in the B-movie horror films directed by Terence Fisher for Hammer Films could fill a book. In fact, there is such a book.

"Family is a force of humanity"

Actually, Spin, adapted by the younger Redford from Donald Everett Axinn’s debut novel of the same name, is an intimate coming-of-age drama set in 1950s small-town Arizona. Starring Ryan Merriman, Stanley Tucci, Dana Delany, and Paula Garcés, it tells the story of an orphan named Eddie (Merriman) whose parents were killed in a flying accident, and who was left by his uncle (Tucci) to be raised by a Mexican employee (Rubén Blades) and his Anglo wife (Delany), a schoolteacher.

Ratings Creep? What Ratings Creep?

In 2002, according to a July 16 Philadelphia Inquirer story ("Film rating trend raises creepy issues"), Nell Minow, a.k.a. the "Movie Mom" and film critic for movies.yahoo.com, went to see the PG-13 rated About a Boy. At one point in the film, Hugh Grant used an adjectival form of what the MPAA calls "one of the harsher sexually-derived words," but is often referred to as "the f-word."

What Are the Decent Films?

Must a decent film deal only with uplifting or wholesome subjects, or may dark or disturbing themes also be dealt with? Can a film include nudity or profanity and still be “decent”? Can “humane culture” include popular films or genres like action films and romantic comedies, or do only highbrow “art films” count as true culture?

Freud, C. S. Lewis, and the Question of God

The Question of God, airing in two parts on PBS September 15 and 22, is an extension of Dr. Nicholi’s course and of his book The Question of God: C. S. Lewis and Sigmund Freud Debate God, Love, Sex, and the Meaning of Life, published by the Free Press. Over the course of its four hours, The Question of God blends biographical surveys of Freud’s and Lewis’s intellectual and metaphysical journeys, panel discussions of believers and unbelievers moderated by Dr. Nicholi, expert interviews with authorities like Peter Kreeft and Harold Blum, and dramatic readings from Freud’s and Lewis’s writings with actors portraying the two thinkers.

The Passion of the Christ: First Impressions (2004)

As I contemplate Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, the sequence I keep coming back to, again and again, is the scourging at the pillar.

Recent

- Crisis of meaning, part 3: What lies beyond the Spider-Verse?

- Crisis of meaning, part 2: The lie at the end of the MCU multiverse

- Crisis of Meaning on Infinite Earths, part 1: The multiverse and superhero movies

- Two things I wish George Miller had done differently in Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga

- Furiosa tells the story of a world (almost) without hope

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.