What Are “Real Movies”?

Borrowing a page from the UK’s Campaign for Real Ale, Roger Ebert blogs from Cannes on the need for a Campaign For Real Movies.

The implicit complaint is the same: In a marketplace glutted with mass-produced product that’s all fizz and no substance, it’s hard to find a hand-crafted product of distinction and local flavor, the kind of product that surprises and challenges you, that engenders real enthusiasm and loyalty. Real Ale is not carbonated or carefully crafted to taste just like every other mass-market brew. Ebert writes:

[Real Movies] also would not be carbonated by CGI or 3D. They would be carefully created by artists, from original recipes, i.e., screenplays. Each movie would be different. There would be no effort to force them into conformity with commercial formulas.

These notions took shape while I was viewing some well-made Real Movies I’ve seen this year at Cannes … These aren’t all masterpieces, although some are, but they’re all Real Movies. None follows a familiar story arc. All involve intense involvement with their characters. All do something that is perhaps the most important thing a movie can do: They take us outside our personal box of time and space, and invite us to empathize with those of other times, places, races, creeds, classes and prospects. I believe empathy is the most essential quality of civilization.

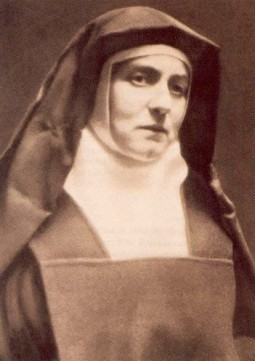

Edith Stein, Saint Teresa Benedict of the Cross, wrote her doctoral dissertation and other treatises on empathy.

That paean to empathy might sound like an overstatement, but St. Edith Stein arguably goes further in her dissertation On the Problem of Empathy and subsequent treatises, arguing that empathy is foundational to personhood and community, to knowledge of others and even knowledge of the self. It is through empathy that the experiences of others become available to us while remaining theirs and not ours. Through empathy I transcend the limits of my own subjectivity and become aware of the subjectivity of another—and understand that my own subjectivity can likewise be the object of another’s empathy. Not only do I gain insight into others from how they perceive themselves, I can also learn from how others see me things about myself I would never otherwise know.

What does this have to do with movies, and with Ebert’s lament for Real Movies? Mainstream Hollywood entertainment, like mass-marketed brews, offer us essentially nothing we haven’t already assimilated long ago. Such movies show us only what we have seen before, tell us only what we already know. Instead of a window into another soul or another world, they offer only a mirror of our existing tastes or (worse) comfort levels. The sequel phenomenon is symptomatic of this. Not that a sequel can’t be surprising and revelatory, but that’s not why sequels get green-lit. They get green-lit because most people are readier to pay for what they already know.

That’s true in spades of mass-market entertainment like this weekend’s Shrek Forever After. But it’s also true of not a few pious movies favored by many in Catholic and Evangelical circles. Many of us are only interested in movies that tell us only what we already know and want to hear: moral messages we already agree with, diagnoses and solutions we already accept for problems we already know about.

Nothing necessarily wrong with that, as far as it goes. Obviously we don’t want to be lining up for movies with moral messages we disagree with! But it’s more complicated than that. I think of a story my mother tells about my father’s early days as a Protestant pastor (he’s a Catholic today) at a church where leading congregants wanted to hear sermons about sin—but only the sins of the younger generation (this was the 1960s). Not sins like gossip, for instance.

A homilist who tells me only what I already know and want to hear does me little good. It’s what I don’t know, and what I don’t know I don’t know, that I most need to hear. For that matter, a movie reviewer that only affirms my existing comfort levels for the kinds of things I like or don’t like in movies does me little good.

A movie is not a homily. What is it? Among other things, a real movie should be an opportunity to see through other eyes. Not first of all the eyes of fictional characters, if it’s a fictional film, but the eyes of the filmmakers. If (and this is a big if) the filmmakers have brought empathy to their movie, if they have looked through the eyes of others and creatively expressed that insight in their characterizations of fictional characters (or their handling of real events), then the film offers an opportunity to share in that empathic experience.

If the filmmakers haven’t brought empathy to their movie, very likely it isn’t worth watching. Nothing is more likely to secure my distrust of a serious adult drama than a clear lack of empathy for a major character, or for a class of characters.

Empathy doesn’t mean excusing bad behavior because the person meant well, or had a bad childhood, or whatever. It does mean understanding that the lowest scoundrel is not a demon or a monster, but a man like ourselves—and perhaps, by understanding the nature of his transgressions, gaining insight into our own capacity for selfishness.

Ebert gave examples from Cannes of the kind of Real Movies he was talking about. I recently saw a Real Movie opening this weekend in New York and LA: Solitary Man, directed by Brian Koppelman and David Levien from Koppelman’s screenplay. Not a movie about another culture or time, it is nevertheless about a world far removed from most of us.

Solitary Man stars Michael Douglas as a man so venal, egocentric and dissolute that to empathize with him might seem almost a temptation to be resisted rather than an occasion of insight and compassion. A disgraced former car dealership mogul whose rapacious behavior has torpedoed his career and his marriage, Ben Kalmen is a compulsive salesman whose first and only product line is himself, and everything is always about making the pitch and closing the deal, especially in the presence of attractive women half or even a third of his age.

Surely a man like this should be censured, not understood? Surely a movie that invites us to see the human side of this contemptible creature is a contemptible film? Or, if not contemptible, at least gratuitously unpleasant, rubbing our noses in depravity to no redemptive end? Or is it, on the other hand, a morality play? An “aging-Lothario-gets-his-comeuppance number,” as David Edelstein put it?

The potential pitfalls are real, and Solitary Man is frank enough about Ben Kalmen’s sleazy inner world to be off-putting to some. But there’s more to it than that. There is empathy not only for Ben but also for those whom he variously uses, wrongs or lets down; we see Ben through the eyes of others as well as through his own, and from this multifaceted perspective emerge larger truths. I’m particularly struck by Ben’s grown daughter struggling to be a daughter to a man who is rotten at being a father (and grandfather) while also protecting her son and being loyal to her husband and to her mother. Then there’s Danny DeVito, embodying decency as an old friend of Ben’s, an unassuming diner owner whose shoe Ben isn’t worthy to untie.

Solitary Man takes some unexpected turns before coming to a crucial fork in the road, a moment of clarity that comes when someone barreling down a one-way road is abruptly faced with a clear choice: to continue or to change direction. In a typical Hollywood confection, the ending would be all what happens as a result of the choice Ben makes for him and everyone else. In Solitary Man, it’s the clarity that matters. We see the truth about who Ben is and why, and what it means for him and those around him. We see the stakes, and so does he.

Shrek Forever After also involves a protagonist who lets down those closest to him for reasons not unlike Ben’s. It’s not a bad movie, in a flattish Coke sort of way. It’s inoffensive and mildly amusing, and in the end you’re the same person you were 93 minutes earlier, with not much to talk about coming out of the theater.

Recent

- Benoit Blanc goes to church: Mysteries and faith in Wake Up Dead Man

- Are there too many Jesus movies?

- Antidote to the digital revolution: Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality

- “Not I, But God”: Interview with Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality director Tim Moriarty

- Gunn’s Superman is silly and sincere, and that’s good. It could be smarter.

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.