The Dark Knight trilogy: The inconclusive battle for Gotham’s soul

The Dark Knight is now ten years old. Viewed together, the three films invite comparison to the story of Abraham and God’s judgment on Sodom — but something is missing: a verdict.

Squint hard enough at almost any popular film, and you can find biblical parallels of one sort or another, often Christological motifs (e.g., death and resurrection). Such parallels are frequently strained and seldom illuminating. Yet I’m struck by the extent to which Christopher Nolan’s celebrated Dark Knight trilogy (of which the monumental second chapter, The Dark Knight, was released ten years ago this week), watched back to back, can be fruitfully considered as an extended comic-book riff on the story of Abraham and God’s judgment on Sodom in the Book of Genesis.

Nolan has said that each film of the Dark Knight trilogy was independently conceived rather than being planned as part of a trilogy, and each film has its own thematic scope. Fear and responsibility are key motifs in Batman Begins. The Dark Knight is dominated by chaos and escalating conflict, while The Dark Knight Rises develops themes of pain and consequences, among others. Nevertheless, the trilogy is linked by a unifying theme defining the conflict between Christian Bale’s Bruce Wayne / Batman and the villains who oppose him. The recurring question: Is there hope for Gotham City? Are its people worth saving? Is salvation even possible? Are there good people here, or is there only corruption and amoral self-interest destroying itself?

Carrying on in his own way the legacy of his philanthropic parents, Bruce seeks to save Gotham, to give it hope, to inspire its people. Like Abraham, he knows the city’s corruptness, but wants to see the city saved and hopes there are enough good people to make it worth saving. Pitted against Gotham’s Dark Knight are villains who not only take God’s place as judge and executioner, but who see themselves as agents of some ultimate reality or supreme principle — in effect, of whatever takes the place of God in their worldviews. For Heath Ledger’s Joker in The Dark Knight, chaos rules. For Ra’s al Ghul in Batman Begins, “balance” or “harmony” is the supreme principle. In effect, the same is true, by proxy, for Bane in The Dark Knight Rises, who wants to finish what Ra’s al Ghul started out of love for the latter’s daughter, Talia.

Judgment on Gotham

The dialogue between God and Abraham, in which Abraham pleads for the city, is echoed most directly in Batman Begins. “Like Constantinople or Rome before it,” intones Liam Neeson’s Ducard, later to be revealed as Ra’s al Ghul himself, Gotham “has become a breeding ground for suffering and injustice. It is beyond saving. … Gotham must be destroyed.” Bruce tries, like Abraham, to negotiate: “Gotham isn’t beyond saving. Give me more time. There are good people here.” How many good people there might be, Bruce doesn’t try to quantify, and there’s no negotiating with Ra’s in any case. The Dark Knight manages to thwart his former mentor’s plans, but judgment has only been deferred, not set aside.

The battle over Gotham’s soul reaches a sort of crescendo in the celebrated last act of The Dark Knight, as the Joker puts his theory to the test with a perversely inspired social experiment. “Their morals, their code … it’s a bad joke,” the Joker insists. “They’re only as good as the world allows them to be. You’ll see — I’ll show you. When the chips are down, these civilized people … they’ll eat each other.” Unlike Ra’s, the Joker is willing, in his sociopathic way, to inquire into just how good or bad the people of Gotham are. It’s like a demented echo of the depiction of Yahweh in Genesis traveling to Sodom to see for himself if the wickedness of the city is as bad as has been reported.

The Joker’s test has the elegance of a moral-philosophy thought experiment. Two ferry boats, one full of commuters and the other full of convicts, are stranded in the river, each burdened with a powerful bomb and each furnished with a detonator — to the bomb on the other boat. The Joker’s ultimatum: One boat must blow up the other boat, or he’ll blow them both up. It almost works as the Joker intends. The majority of citizens on the civilian boat vote to blow up the prisoner boat, but none of them can bring themselves to push the button. The warden on the prisoner boat likewise wants to blow up the civilian boat, but can’t. It may be less a matter of moral conviction than timidity or squeamishness, but the code of civilization goes a millimeter deeper than the Joker calculated. These people might want to eat each other, but they just can’t do it.

This otherwise rather hollow moral victory is dramatically deepened by a real act of heroism: An intimidating prisoner approaches the warden, demands the detonator from him, and throws it out the window into the river before retreating to pray silently with his fellow convicts. Completing the failure of the Joker’s experiment, Batman surprises the Joker and prevents him from blowing up the ferries. The convict’s heroism, at the climax of so dark and twisted a tale of nihilism and chaos, is a powerfully galvanizing, cathartic moment. It even gives a glimmer of truth to Batman’s retort to the Joker: “This city just showed you it’s full of people ready to believe in good.”

But the Joker hasn’t really lost. “You didn’t think I’d risk losing the battle for the soul of Gotham in a fistfight with you?” he taunts Batman. The Joker’s ace in the hole: Gotham’s Dark Knight might be incorruptible, but the Joker has corrupted the city’s “white knight,” D.A. Harvey Dent, in whom Bruce himself had put his hope for a hero to replace his alter ego. The revelation of Dent’s fall, the Joker says, will break completely the spirits of the people and plunge Gotham into darkness.

Hoping to save Gotham’s soul from the Joker’s gambit, Batman chooses to become the fall guy for Dent’s destruction. At Batman’s bidding, Commissioner Gordon publicly indicts the Dark Knight for the white knight’s murder spree, even claiming that Batman murdered Dent himself in cold blood. By this “noble” lie, Batman hopes, Dent the legend might become the hero Gotham needs in a way that Dent the man couldn’t. This denouement seals what should already be apparent: The failure of the Joker’s experiment, a single act of heroism from one prisoner and the weakness of two other men, is inconclusive. Gotham’s soul still hangs in the balance; it is not yet saved. Once again, judgment has been deferred. What will happen if and when the people of Gotham learn the truth? We still don’t know whether the city is worth saving.

Power to the people?

Further confirmation comes in The Dark Knight Rises, a movie that ostensibly makes more of the people of Gotham than either of its predecessors. “The people of our greatest city are resilient,” declares the U.S. president as Gotham faces its greatest test. “They have proven this before; they will prove this again.” As the president speaks, the entire city has been taken hostage by Tom Hardy’s Bane, a mercenary who wants to finish Ra’s al Ghul’s work of destruction by repeating the Joker’s experiment on a citywide scale.

Taking the city hostage with a neutron bomb, Bane nevertheless professes publicly to be a liberator, not a conqueror. “We take Gotham from the corrupt,” he says. “The rich. The oppressors of generations who’ve kept you down with the myth of opportunity. And we give it to you … the people. Gotham is yours; none shall interfere. Do as you please.” His real intentions are quite different. “There can be no true despair,” he tells Bruce, “without hope. So as I terrorize Gotham, I will feed its people hope to poison their souls. I will let them believe they can survive so that you can watch them clamber over each other to stay in the sun.”

Before Bane’s attack, Gotham had become physically safer than ever in the eight years since The Dark Knight, thanks to a tough-on-crime bill called the Dent Act, which empowered authorities to break the back of the city’s organized crime. This new era of law and order is tarnished, of course, by the passing of the Dent Act on the strength of Batman’s “noble” lie about Dent — a fact that comes back to haunt Gordon when Bane reveals publicly that Gordon was unwilling to trust the people of Gotham with the truth. As for the law itself or what might be wrong with it, we learn very little beyond Bane’s claim that countless inmates in Blackgate Prison have been denied parole.

Judgment by fire

Bane says will detonate the neutron bomb there is any outside interference or if anyone flees the city. In reality, the bomb will eventually detonate on its own. As Abraham’s negotiation with God found a dim echo in Batman Begins and as God’s examination of Sodom found a twisted parallel in The Dark Knight, The Dark Knight Rises roughly corresponds to Sodom’s judgment by fire.

In this case, of course, judgment is averted — and here’s where Gotham’s story parts decisively with that of Sodom. Sodom was destroyed; Gotham is spared. Does that mean it was saved? Are the people of Gotham finally vindicated? Alas. In the end, it seems how the ordinary people of Gotham acquitted themselves in those months of anarchy was a matter of as much indifference to Nolan as to Bane. During those months, the streets of Gotham are ruled, not by mobs of citizens, but by Bane’s army of liberated prisoners from Blackgate (convicts far less noble than those on the ferry in The Dark Knight). Opposing them, on the other hand, are not citizens rising up to defend their city, but only the police.

As for the ordinary people of Gotham, over whose souls Batman and his foes have wrestled for three films, they appear to do very little but keep their heads down. Neither the “clambering over one another” that Bane promised nor the “proven resilience” the president invoked materializes in any dramatically important way. There’s some looting, though whether it’s all Bane’s army of convicts or ordinary people in the street involved is unclear. There’s certainly no sign of people in the streets organizing to take back their city or to oppose Bane in any way. Instead, The Dark Knight Rises culminates in a war in the streets between lawless criminals and heroic police officers: a kind of redo of the last eight years, albeit without the benefit of the Dent Act.

In my 2012 review of The Dark Knight Rises I noted that, for all the September 11 and “War on Terror” motifs woven through the Dark Knight trilogy, there’s no United 93 moment: no moment of ordinary citizens banding together to defend their turf and spit in the eye of terror. Nolan’s latest film offers another point of contrast: What the trilogy lacks is precisely some meaningful display of “Dunkirk spirit”: of solidarity emerging from a shared crisis, prompting ordinary people (not trained, uniformed police officers, but hoi polloi) to rise to the occasion in some extraordinary way. At times, it almost looks like a civilian resistance is coming, as when Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s young cop, John Blake, furtively chalks what looks like the “bat symbol” on city walls. “The idea was to be a symbol,” Bruce tells Blake. “Batman could be anybody. That was the point.” Perhaps he could even be everybody. But the “Bat resistance” never rises to the occasion.

‘You mess with all of us’

Earlier superhero movies offer brief glimpses of what’s missing here, as when crowds of ordinary people in Superman II and Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man movies take on the supervillains after the hero has been taken down. Of course the Metropolis residents don’t have a prayer against the Kryptonian supervillains, but the mob on the Queensboro Bridge pelting the Green Goblin with debris aren’t to be trifled with. “You mess with Spidey, you mess with New York!” shouts one, while another adds, “You mess with one of us, you mess with all of us!” Then there are the passengers on the El train in Spider-Man 2, who not only save the webslinger’s life after he saves theirs, and give him back his lost mask with a promise to protect his identity, but attempt to defend him from Doctor Octopus. While their resistance is as useless as that of the Metropolis residents, their solidarity with Spidey is genuinely touching.

By contrast, this summer’s Incredibles 2 contemplates the notion that superheroes, far from inspiring ordinary people to rise to face challenges, instead have an enervating, numbing effect. In a long monologue, the villainous Screenslaver accuses the masses of complacently sitting back, looking for supers to do everything for them, like children looking to their parents. While the film doesn’t necessarily endorse this philosophy, it doesn’t refute it either. Like the Dark Knight films, though far less pointedly, Incredibles 2 indicts the masses but doesn’t render a verdict. Ordinary people aren’t given an active role one way or the other — a kind of verdict in itself, perhaps.

The Dark Knight trilogy is tonally very different from the likes of the Superman and Spider-Man movies, and certainly any civilian resistance in Gotham would have looked very different from these scenes. Had Nolan pulled it off, he could have gone beyond the thought-experiment heroism of the ferry prisoner to realms of genuine heroism and inspiration.

The Dark Knight Rises is linked in many people’s minds with the mass shooting in Aurora, Colorado that took place at a midnight screening on opening day. Of the 12 people who were killed, three were young men who reportedly died shielding their girlfriends with their bodies. (It was after this shooting that I first saw Mr. Roger’s now-famous quotation about “looking for the helpers” widely circulating on social media.) That’s the kind of spontaneous heroism that should have been on the screen, not just in the theater. The trilogy needed it. We viewers need it, too.

Related

Caped crusaders and the common good

Questions around how what people need and deserve and how they should be governed are of course recurring themes in the saga of Zorro’s more famous heir, Batman … We don’t look to superhero movies to answer these questions for us, but their varying answers tell us something about ourselves and the times in which they were made.

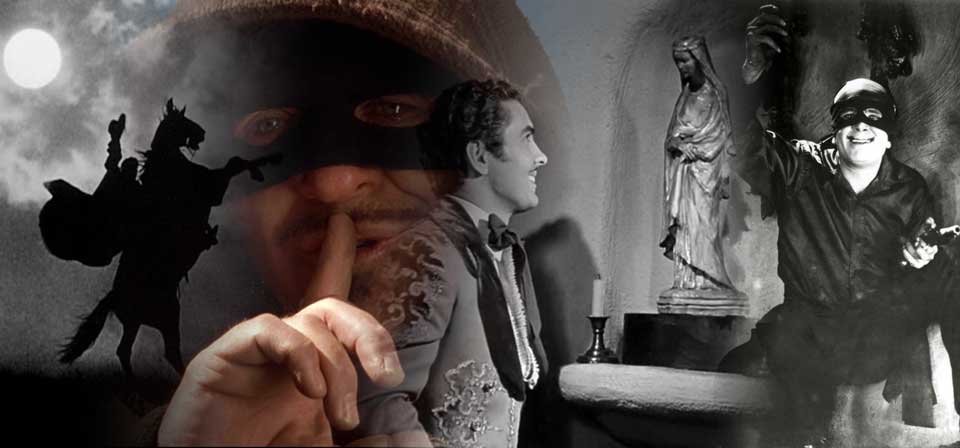

Zorro: Before Daredevil or Nightcrawler, the first superhero ever was Catholic

“He has been many different men,” Antonio Banderas tells Catherine Zeta-Jones in the last scene of the rousing 1998 action movie The Mask of Zorro.

Recent

- Benoit Blanc goes to church: Mysteries and faith in Wake Up Dead Man

- Are there too many Jesus movies?

- Antidote to the digital revolution: Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality

- “Not I, But God”: Interview with Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality director Tim Moriarty

- Gunn’s Superman is silly and sincere, and that’s good. It could be smarter.

Home Video

Copyright © 2000– Steven D. Greydanus. All rights reserved.